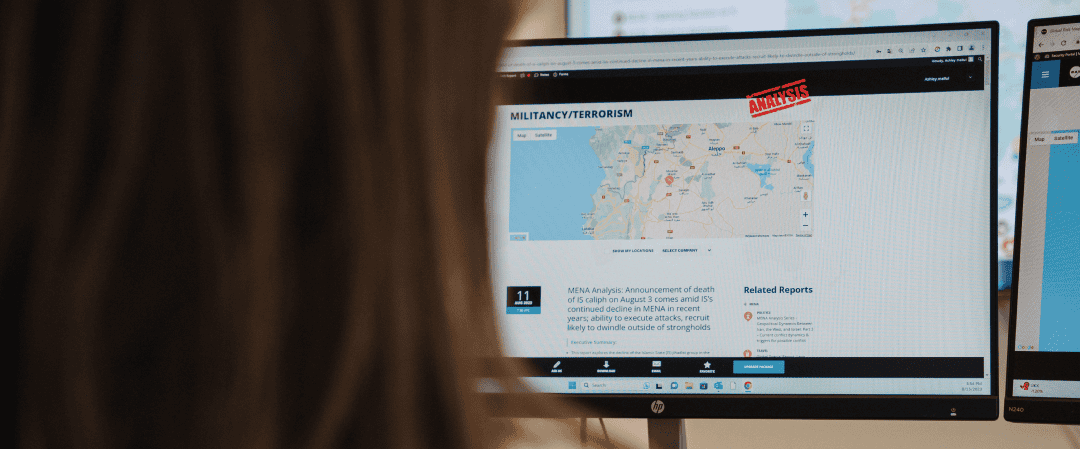

MAX Intelligence: Iran Sanctions Snapback – Escalation Risks & Security Impacts

- MAX Security

Table of Contents

Iran’s 27 September snapback sanctions trigger high risks of nuclear escalation, maritime insecurity, and arbitrary detentions.

Executive Summary

-

Since the August 28 activation of the snapback mechanism by the E3 parties (the UK, Germany, and France), procedural milestones have narrowed the options to prevent the automatic reimposition of UN sanctions on Iran at the end of September.

-

The September 19 UNSC resolution, backed by only four members, underscored Tehran’s limited options and confirmed the near inevitability of reimposed sanctions.

-

Iran will consider its response once snapback sanctions are reinstated. Several options may be employed in parallel and in a calibrated way, designed to exact a price from the West and regain some of its leverage, without engaging in direct conflict.

-

Possible responses include halting IAEA cooperation, an incremental escalation of nuclear activity, expanded reliance on China and Russia, and asymmetric hostile actions that are more likely to manifest at sea.

-

The risk of arbitrary detentions of Westerners in Iran, particularly of US, French, German, and British nationals, will be compounded.

-

Avoid all travel to Iran at the current juncture and anticipate increased risks to European (specifically British, German, and French) interests in and around the country.

Assessments & Forecast

UNSC rejects resolution to delay snapback sanctions, eliminating final procedural hurdle before September 27 deadline

-

Since August 28, when the snapback mechanism procedure was activated, the process has carried an air of inevitability. The question was not whether sanctions would return, but how different states would maneuver in anticipation of that outcome. The first major milestone came on September 7, when the ten-day window to extend sanction relief expired without any resolution being submitted. Even Russia and China, Iran’s supporters who object to the E3 measures, refrained from tabling a text they knew would be vetoed. Their inaction underscored Tehran’s limited diplomatic options, especially its inability to rely on its Eastern allies to resist the re-triggering of sanctions.

-

Around the same time, a confidential IAEA report indicated that Iran possessed 440.9 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent (as of June 13). The findings reaffirmed that Tehran continues to possess a quantity of material sufficient, if further enriched, to produce multiple nuclear devices. This was also confirmed by Israeli Prime Minister (PM) Benjamin Netanyahu in an interview he gave in August, in which he admitted that Tehran’s stockpile of highly enriched uranium was not targeted during the Iran-Israel war in June.

-

Parallelly, since the war, the absence of any credible mechanism to monitor or account for this stockpile has reinforced Western concerns over Iran’s deliberate opacity. The IAEA report, therefore, reinforced E3 views that partial measures cannot substitute for full compliance with safeguards.

-

Although Iran sought to showcase cooperation by reaching an agreement with the IAEA, the arrangement allowed only selective and delayed access, leaving safeguards incomplete. Tehran presented the deal as a demonstration of cooperation, outlining “modalities” for renewed inspections across all facilities, including those struck by Israel and the US in June. However, the agreement lacked clear deadlines and made access dependent on approval from the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), allowing no immediate entry beyond the Bushehr facility. Safeguards were not fully restored but restricted to reports and case-by-case access. Iranian Foreign Minister (FM) Abbas Araghchi clarified that inspectors would only gain broader access “at an appropriate time,” underscoring Iran’s intent to retain maximum control and illustrating the selective nature of cooperation. This selective framing reflects Tehran’s strategy to project responsiveness while withholding the full safeguards compliance repeatedly demanded by the E3. European capitals increasingly interpret these measures as tactical maneuvers to buy time rather than genuine moves toward transparency.

-

This pattern of tactical gestures continued through mid-September. On September 17, Foreign Minister Araghchi floated a “reasonable plan” for interim talks and eventual dilution of its uranium stockpile in exchange for US guarantees and sanctions relief. An unconfirmed September 19 report indicated two steps: resuming talks for an interim deal to retrieve and dilute the 60 percent stockpile, and extending Resolution 2231 to allow “time and space” for dialogue. The roadmap envisaged eventual dilution to 20 percent in exchange for a US security guarantee and sanctions relief. While appearing to meet E3 conditions on paper, IAEA cooperation, stockpile clarity, and renewed US engagement, the plan fell short in practice. US engagement was confined to a narrow interim track rather than comprehensive nuclear talks, and stockpile action was limited to a roadmap rather than immediate dilution. The proposals reflected Tehran’s preference for symbolic concessions over binding commitments and were dismissed by European officials as largely insubstantial. It likely also strengthened their assessment that snapback sanctions and coercive instruments remain the only viable means of addressing Iran’s nuclear program.

-

Iran’s diplomatic efforts beyond the UN Security Council (UNSC) also faltered. On September 18, Tehran was reportedly forced to withdraw a resolution at the IAEA General Conference aimed at banning attacks on nuclear facilities after failing to muster support, reportedly due to US lobbying. Coupled with the minimal four votes it later received in the Council, the move highlighted the limited reach of Iran’s diplomatic coalition. Moscow and Beijing continued to provide rhetorical cover but proved unable to alter outcomes in international forums.

-

The decisive turning point arrived on September 19, when the UNSC presidency (South Korea) introduced a draft resolution to block snapback. It collapsed with the support of only four members- China, Russia, Pakistan, and Algeria. The result reflected both Resolution 2231’s design, which favors sanctions in the absence of consensus, and Iran’s mounting isolation in the Council. By this point, European leaders had already made their stance clear. The EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Kaja Kallas, warned that the window for diplomacy was closing, while French President Emmanuel Macron flatly declared that snapback would proceed, dismissing Iran’s overtures as unserious. These statements underscore the European powers’ assessment that Tehran’s latest offers are inadequate, signaling that the window for compromise has effectively closed. Rather than indicating ongoing deliberation, this language reflects a European consensus that sanctions will be reimposed at the end of September, irrespective of Iran’s recent efforts to get concessions.

-

The September 19 UNSC vote effectively removes any remaining procedural avenues to avert this outcome, while explicit statements by senior European leaders underscore that the reimposition of sanctions is all but certain.

-

Iran is still in a weakened geopolitical position following the 12-day war with Israel, and it will likely contemplate several avenues of action designed to increase its leverage and exact a price from the involved parties.

Scenarios

None of the scenarios outlined below should be ruled out. Several are likely to be pursued in parallel, at least partially, and they are not mutually exclusive. Tehran’s messaging since late August has emphasized that cooperation with the IAEA is conditional and reversible, that the snapback sanctions will cause “irreparable damage,” and that retaliation will follow once sanctions are restored. At the same time, Iranian officials continue to stress that negotiations remain possible, underscoring that, while retaliation is highly plausible, it will likely remain calibrated. Hence, continued or renewed talks with Western countries remain a strong possibility, even as the September 19 UNSC vote virtually confirmed the return of sanctions.

The sanctions set to be reimposed are formally targeted at arms, missiles, and nuclear activities, but also contain provisions with broader economic impact. They reinstate embargoes on conventional weapons, restrictions on ballistic missile development, prohibitions on nuclear-related technology transfers, and asset freezes on defense-linked individuals and entities. They also extend to financial institutions, shipping and transport networks, and technology transfers with dual-use purposes. Although less comprehensive than the “maximum pressure” campaign restored by US President Donald Trump, which focused on illicit oil exports and shadow banking networks, the measures still reinforce Iran’s financial isolation and create compliance risks. The continued depreciation of the rial, reaching a record low as the dollar rate surpassed 1,060,000 Iranian Rials (IRR) on September 22, combined with ongoing energy and water crises and US punitive measures, underscores the vulnerability of Iran’s economy.

Political/Diplomatic Iranian Response

Scenario 1: Suspension of IAEA cooperation

-

The September 9 agreement between Tehran and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was initially hailed as a breakthrough; however, its content and clarifications reveal that it functions more as a conditional bargaining instrument than a binding commitment to transparency. On September 14, the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) approved the arrangement but explicitly warned that it would be voided in the event of “hostile actions,” including snapback sanctions. This position mirrored FM Abbas Araghchi’s remarks on September 11, stating that the deal holds only if “no hostile action is taken against Iran,” and was reinforced by Deputy Foreign Minister Kazem Gharibabadi on September 19.

-

The consistent framing makes clear that Tehran views IAEA cooperation as a leverage tool, readily reversible should sanctions return. The probability that Iran will significantly curtail IAEA access and entirely terminate the agreement once snapback is enforced is very high.

Scenario 2: Continued diplomatic engagement

-

Despite the procedural collapse at the UN, Tehran continues to signal at least some willingness to engage in dialogue under certain conditions, particularly the receipt of security assurances from the US and the removal of some economic sanctions. FM Araghchi argued on September 11 that snapback sanctions would strip Europe of its “last tool on the nuclear issue.” A semi-official outlet further reported on September 22 that Araghchi is expected to meet E3 and EU counterparts in New York on September 29 or 30.

-

This dual-track strategy, threatening retaliation while preserving diplomatic channels open, reflects Tehran’s need to maintain maneuvering space, particularly if less escalatory measures (such as ending IAEA cooperation) are exhausted. The precedent of July 2, when Iran ended IAEA cooperation while continuing to engage diplomatically with the E3, underscores this approach. The likelihood of continued conditional diplomacy is high, and it may proceed in parallel with limited hostile measures.

Scenario 3: Expanded sanctions evasion via China and Russia

-

The likelihood of expanded sanctions evasion via China and Russia is very high. Snapback sanctions will push Tehran further into dependence on China and Russia, a trend already evident under existing US restrictions. This reflects both necessity and structural constraints, given that US sanctions already substantially restrict Iranian access to global financial and energy markets and that snapback sanctions will further limit its military and nuclear industries.

-

China already accounts for over 90 percent of Iran’s oil exports, often imported through “teapot refineries” and shadow fleets. Iran provides critical UAV technology to Russia, and the two countries have strengthened their defense cooperation, particularly following the breakout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Tehran and Moscow signed an agreement on September 24 to expand their nuclear energy cooperation, with a focus on constructing eight new nuclear power plants in Iran by 2040. The memorandum of understanding formalizes plans to develop both small modular reactors and full-scale nuclear power plants. It builds on decades of cooperation, including Russia’s completion of the Bushehr nuclear facility, which remains Iran’s only operational reactor with an approximate capacity of one gigawatt.

-

Iran will be incentivised to further invest in its “Look to the East” policy and deepen its cooperation mechanisms with eastern allies, particularly Russia, China, Belarus, and Venezuela. This may enable Iran to evade targeted sanctions.

Nuclear Program Responses

Scenario 1: Incremental or limited nuclear escalation

-

Iran has consistently expanded its nuclear program and uranium enrichment, even during negotiations with the US, and despite the significant losses it incurred during the 12-day war with Israel, it retains the capacity to reconstitute nuclear activity. This is primarily based on Iran’s relatively well-developed national science and engineering infrastructure, which provides Tehran with technological and industrial depth in the long term. This assessment was also expressed by IAEA Director Rafael Grossi, who on June 27 indicated that Iran could potentially resume enriching uranium with a few cascades of centrifuges within a few months if it wished to. Together with the fact that Iran retains the stockpile of above 400kg of uranium enriched to 60 percent, this makes incremental escalation a credible pathway.

-

Such a pathway would also entail risks for Iran, given repeated Israeli and American threats to thwart such activities if they are spotted. Consequently, an Iranian intensification of specific nuclear project-related activities is likely to be gradual and measured, with Iran proceeding incrementally to maintain strategic leverage while trying to keep a low profile and to avoid actions that could provoke immediate international retaliation. The more practical measures for Iran in this context would likely entail the quiet deployment of centrifuge cascades at undeclared sites.

Scenario 2: Withdrawal from NPT

-

Iranian officials have repeatedly raised the possibility of withdrawing from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) if the snapback sanctions are implemented, with a parliamentary proposal toward this goal already proposed in response to the activation of the mechanism. FM Araghchi emphasized that while this is not Tehran’s only measure on the table, “withdrawing from the NPT has been raised as an option.” Such threats are likely intended to underscore the potential severity of Iran’s response, even if withdrawal would not be the most immediate course of action. Withdrawal would dismantle the legal basis for IAEA oversight, erase safeguard obligations, and signal Iran’s rejection of international restrictions on its nuclear program. This aligns with Tehran’s narrative that Western violations of the JCPOA render continued compliance untenable.

-

Russia and China, while politically supportive of Tehran, are unlikely to endorse such a move, given their longstanding emphasis on the centrality of the NPT to global non-proliferation, creating a disincentive for Tehran.

-

Furthermore, the withdrawal may be used by Israel and the US to justify renewed military action, framed as preventive measures against a country openly disavowing nuclear non-proliferation. The precedent of North Korea, which withdrew in 2003 and developed nuclear weapons within three years, underscores how such a move would be interpreted. Against this backdrop, the likelihood of Iran following through with withdrawing from the NPT is low in the immediate term, but the consistent rhetoric is indicative that the option remains.

Asymmetric Responses

Scenario 1: Hostile measures outside the nuclear framework

-

In addition to nuclear measures, Tehran retains several asymmetric tools that allow it to impose costs while avoiding direct military confrontation with the West. The most significant risks of escalation lie in a maritime campaign aimed at disrupting global energy supplies, pressuring Western economies, and signaling Iranian resolve amid international isolation. In the Persian Gulf, Iran has repeatedly leveraged maritime insecurity, such as in 2019 when it sabotaged oil tankers and seized foreign vessels following the US’ withdrawal from the nuclear deal. Similar tactics remain available today. Tehran may designate the E3 as “hostile states,” authorizing the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN) to inspect vessels bound for or flagged by these countries.

-

Selective harassment and boarding operations could accompany this to increase volatility at sea. Iran’s motivation in this respect could also be to drive up global oil prices, given its influence in the Strait of Hormuz, a chokepoint that handles roughly 20 percent of seaborne oil exports, working in its favor

-

Iran can also significantly escalate GPS jamming and spoofing as part of its maritime retaliation. The country has already demonstrated sophisticated capabilities in this domain, affecting nearly 1,000 ships per day in the Arabian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz during the June Israel-Iran conflict. This ability to scale operations provides Iran with a potent asymmetric tool that can inflict economic damage while maintaining plausible deniability. Given the Persian Gulf’s role as a global energy chokepoint, even limited interference can have a significant impact, making GPS disruption one of Iran’s preferred instruments.

-

Iran’s key ally, the Yemen-based Houthis, may also demonstrate a degree of coordination and support to Iran, and it cannot be entirely ruled out that they would expand their target bank at sea, trying to target commercial vessels linked to E3 parties. This would be based on a logic that the Houthis have risen to prominence as the most significant and active actor in Iran’s regional Axis of Resistance and that they would wish to help Tehran exact a price from the Western states responsible for reintroducing extensive sanctions on their most cherished ally.

-

Responses from Iran’s other regional allies are likely to be limited. Iran-backed militias in Iraq face pressure from Baghdad, restricting their ability to strike US forces or allies without domestic repercussions. In Lebanon, Hezbollah remains constrained by ongoing disarmament efforts and is unlikely to risk confrontation that could weaken its position.

-

Iran is also liable to intensify cyber operations against Western infrastructure. Cyber warfare is among Iran’s most preferred methods of targeting rivals, as it enables the Iranian government to inflict damage on both private and public sector interests while preserving plausible deniability. This allows Iran to limit the risk of broad escalation. Iran has expanded this campaign since October 2023 and increasingly targeted the E3. Tehran also retains the capacity to pursue sabotage or covert activity on foreign soil. The July 15 warning by UK counter-terrorism authorities of a sharp rise in Iran-linked “threat-to-life” operations, including espionage and assassination attempts in the UK, underscores Iran’s intent and capabilities in this domain. Such measures also provide Tehran with a degree of plausible deniability, increasing its attractiveness.

-

Iran will likely be further incentivized to resort to the arbitrary detention of dual nationals or Western citizens on Iranian soil, particularly citizens of E3 states, as a low-cost but high-impact bargaining tool. By detaining individuals on vague national security charges, Tehran can extract diplomatic concessions while signalling resolve at home. This tactic imposes political pressure on Western governments, but it carries risks of reciprocal measures, strained bilateral relations, and targeted sanctions.

Overall, Tehran is likely to pursue measures that signal its capacity to impose costs while maintaining plausible deniability and avoiding a full regional escalation. Even so, these actions would elevate tensions, further isolate Iran, and harden Western positions. Designating the E3 as “hostile states,” while symbolically significant, could provoke reciprocal measures that disrupt Iran’s shipping networks, both legal and illicit, and strain its economy. Such responses might include intensified interdiction of Iranian tankers under the Proliferation Security Initiative, with snapback sanctions providing added legitimacy for targeting illicit trade and acquisitions linked to Iran’s missile and nuclear programs. They could also encompass broader financial sanctions, blacklisting of shadow fleet vessels, asset freezes, and technology restrictions, further raising the cost of Iranian oil exports and challenging its sanctions-evasion networks.

Recommendations:

Iran

-

Avoid traveling to Iran at this time due to escalating tensions between Iran and the West.

-

Remain cognizant of the elevated risk of arbitrary detentions in Iran, especially during heightened tensions between Iran and Western states. This risk is particularly relevant to US, German, British, and French nationals.

-

Remain cognizant of the reimposition of sanctions on Iran and their business-related ramifications, and anticipate a continued decline in Iran’s economy.

Persian Gulf, Strait of Hormuz, Gulf of Oman, Red Sea, Gulf of Aden

-

Remain cognizant of increasing tensions between Iran and the West, which could translate into attempts to disrupt maritime shipping around Iranian waters.

-

Remain as distant as possible from Iranian territorial waters.

-

Take precautions to mitigate the risks associated with GPS jamming and spoofing at sea, particularly in the vicinity of the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz.

-

Monitor the Houthis’ response to the imposition of sanctions on Iran and anticipate the potential expansion of Houthi assaults on commercial vessels in the Gulf of Aden and Red Sea.

-

Remain apprised of UKMTO and US DOT Maritime Administration-issued notices, as well as being aware of NATO Shipping Center alerts.

Cyber

-

Businesses operating in the US, Israel, and other Western countries Iran defines as adversaries, particularly those with links to respective government institutions and/or strategic civilian infrastructures, are encouraged to review and enhance their cybersecurity protocols.

-

Ensure that robust contingency planning is in place to mitigate disruptions caused by potential cyberattacks targeting essential services, including energy, transportation, healthcare, education, and communication networks.

-

Both government and private entities are advised to ensure that employees are regularly informed and trained on best practices for maintaining robust cybersecurity practices.

-

To maintain cyber-safe practices, businesses are recommended to advise their employees to routinely change passwords and password-protect all devices that connect to the internet.

-

Businesses are also advised to regularly update their anti-virus software and computer programs, while backing up critical data. Computer users are also advised to perform comprehensive software updates via their computer’s automated process or from the official provider website to protect against viruses.

-

Avoid clicking on all suspicious links or opening emails from unidentified senders.

-

Review privacy settings on social media platforms to ensure that personal information is not publicly shared and cannot be exploited.

-

Corporations are advised to increase employees’ awareness of cyber campaigns. This may include training personnel on the identification of avatars, social engineering campaigns, common misinformation strategies, and establishing clear guidelines for dealing with phishing attempts and malicious links.

-

Follow updates of local cyber authorities. Remain cognizant of the elevated risk of Iranian cyberattacks amid periods of increased geopolitical tensions, especially involving Israel and the US.

SCOUT

INTEL AI BY MAX SECURITY

Fill in your details to schedule a demo with our team.