Essential Resources for

Security Leaders

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: Trump’s 2025 Immigration Crackdown

May 2025

A detailed analysis of Trump’s 2025 immigration agenda, highlighting enforcement measures, social media vetting, labor risks, and diplomatic visa restrictions.

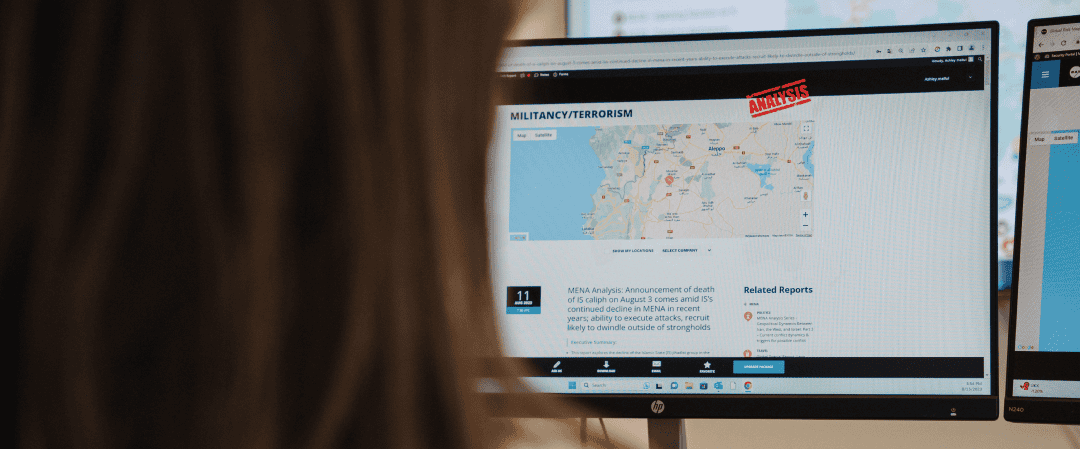

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: Hezbollah UAV Threat in Europe

May 2025

A detailed analysis of Hezbollah’s drone-manufacturing networks in Europe, highlighting logistical sophistication, financial operations, and potential threats of attacks targeting Israeli and Jewish sites.

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: Marine Le Pen Verdict – Impacts on France’s Political Stability

April 2025

A detailed analysis of Marine Le Pen’s conviction and its impact on France’s political stability, highlighting risks of no-confidence motions, far-right disunity, and evolving protest dynamics.

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: HTS in Syria – Strategic Risks & Iranian Threats Facing Jordan

March 2025

The HTS-led transition in Syria introduces new security risks for Jordan, including potential Iranian smuggling routes and domestic radicalization threats.

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: Trump’s Middle East Policy: Sanctions, Arms Deals & Israel Ties

February 2025

Explore how President Trump’s return could reshape US policy in the Middle East — from renewed Iran sanctions to arms deals and normalization efforts with Israel.

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: Germany Election 2025: Parties, Leaders & Security Risks

January 2025

A deep-dive into Germany’s 2025 federal election: key contenders, voter issues, foreign meddling threats, and forecasts for political violence and coalition outcomes.

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: US-China Tensions to Rise Over Green Tech Product Tariffs

September 2024

This report covers the September 2024 tariffs on Chinese green technology products, analyzing the reasons and potential supply chain disruptions amid US-China trade tensions.

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: US Election 2024 Special Report

August 2024

This report covers the Democratic National Convention (DNC) on August 19-22, 2024, analyzing key speeches, policy shifts, and election strategies.

INTEL REPORT

MAX Intelligence: Venezuela Analysis

July 2024

Maduro’s likely victory in Venezuela’s July 28th elections could trigger unrest, with opposition claims of fraud threatening to destabilize the region.

IT’S A TOUGH WORLD