MAX Intelligence: Libya’s Oil Bidding Round Sparks Risks Amid Political Divide

- MAX Security

Table of Contents

Libya’s long-awaited oil bidding round attracts investors—but political fractures, militia unrest, and security risks threaten the future of exploration.

Executive Summary

-

The National Oil Corporation (NOC) and the Government of National Unity (GNU) have launched Libya’s first public bidding round for hydrocarbon exploration in 17 years.

-

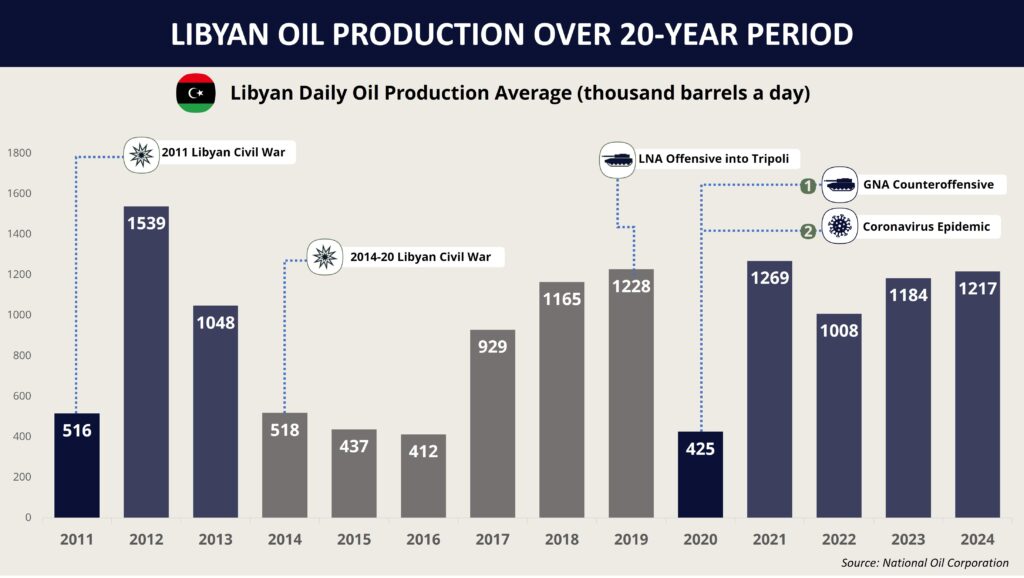

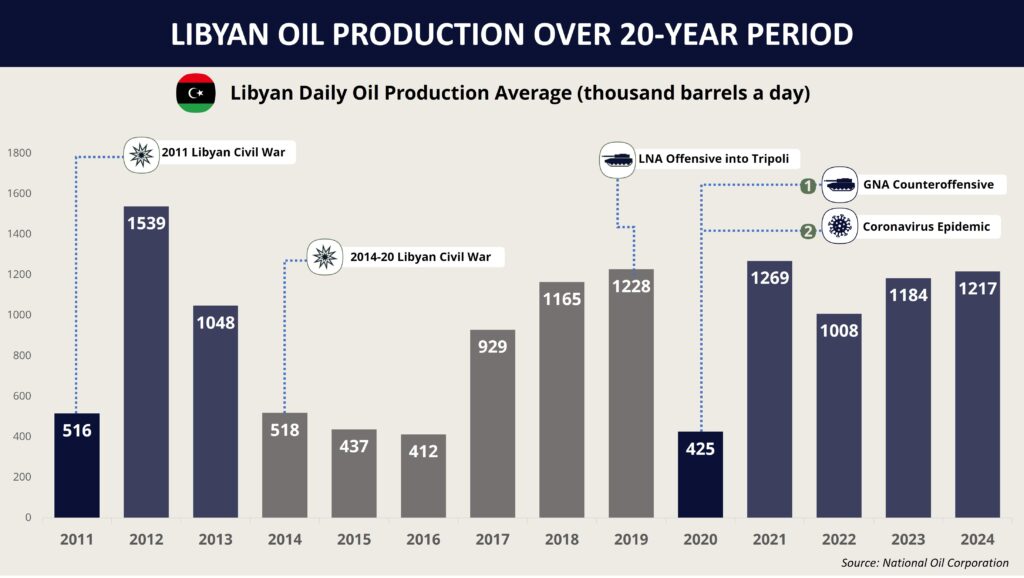

This follows a steady recovery in hydrocarbon production, which reached 1.4 million barrels per day in December 2024, driven by the stabilization of the security environment, infrastructural development and the resumption of activities by several international oil companies (IOCs).

-

Most of the blocks on offer are located in Libyan National Army (LNA)-controlled territory, requiring coordination with eastern Libya-based governing authorities for successful operations. However, political fragmentation, potential local protests, and regulatory objections from eastern authorities pose risks of contract disputes, invalidation, or expropriation.

-

While Tripolitania remained relatively stable in early 2025, the killing of a prominent militia leader in May triggered renewed tensions. This instability, along with incidents such as the NOC headquarters breach in Tripoli and ongoing unrest in Zawiyah, increases threats to oil infrastructure.

Recent Developments in Libya’s Oil Sector

-

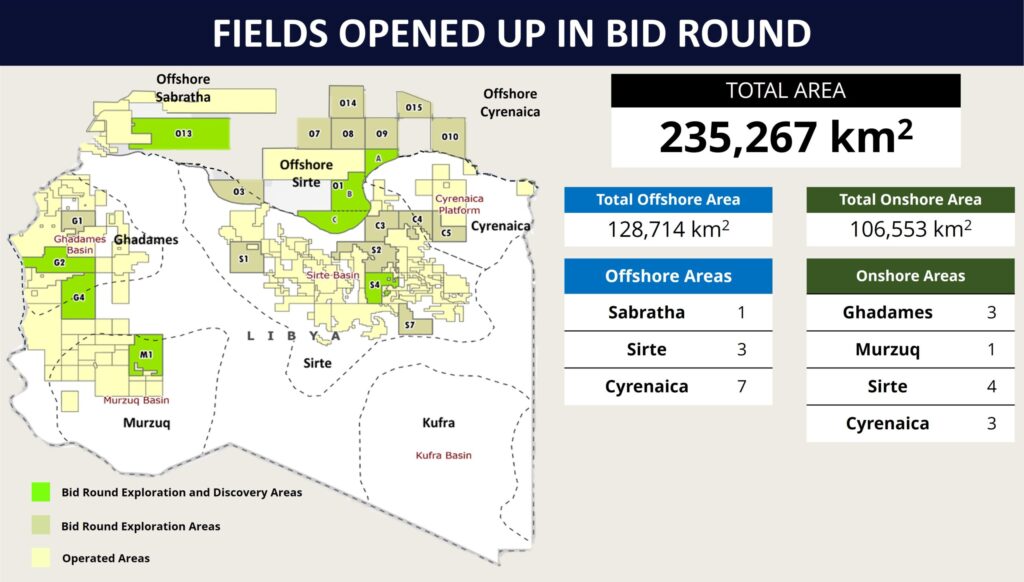

On March 3, the NOC announced in Tripoli its first bidding round for oil exploration, opening up 22 fields for exploration across Libya, both offshore and onshore.

-

In March-April 2025, the NOC conducted four roadshows in Tripoli, Houston, London, and Istanbul to attract bids from international oil companies for hydrocarbon exploration.

-

Unconfirmed reports from March 15 indicate that Salama al-Ghweil, Chairman of the Benghazi-based Competition and Anti-trust Council, sent a letter to NOC Chairman Massoud Suleiman, warning of legal risks tied to contracts signed during the current period of political division. Al-Ghweil also warned that if the NOC continued to issue tenders or conclude contracts, they would document the “violations” and initiate legal action.

-

On March 3, the National Consensus Bloc of Libya’s High Council of State (HCS) released a statement expressing concern over the NOC’s exploration tender. The bloc challenged the legitimacy of launching the tender under what it described as an “expired government” and warned of possible legal action against individuals allegedly responsible for violations affecting Libya’s economy, security, and energy sector.

-

On March 3, the Energy Committee of the Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR) sent a letter to the NOC Chairman demanding full disclosure on the tender process. The committee implied that any tender issued without its authorization would be considered invalid.

-

On June 25, the NOC signed an MoU with the Turkish state-owned Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO) to conduct geological and geophysical studies of four offshore areas.

-

On July 7, British Petroleum (BP) signed an MoU with the NOC to evaluate development of the Sarir and Messla oil fields, along with exploration in adjacent areas. Additionally, the NOC claimed that BP had stated intentions to resume operations in Libya and reopen its office in Tripoli within the fourth quarter of 2025.

-

On August 4, the NOC signed an MoU with US-based ExxonMobil to conduct detailed technical studies of four offshore blocks near the northwest coast and the Sirte Basin.

Overview & Outlook

GNU announces new revenue model

-

The new Production Sharing Agreement (EPSA-V) model introduces significant changes from the previous Exploration and Production Sharing Agreement (EPSA-IV) framework, which granted the NOC a larger share of production (approximately 70–90 percent) and placed the full burden of exploration costs on IOCs. While the contractor will continue to solely bear the costs, the updated model sets a fixed rate for cost recovery, increases the internal rate of return for contractors, and implements faster profit-sharing with the NOC. These measures collectively aim to shorten the investment payback period, expedite cost recovery, and enhance profitability, ultimately improving the sector’s attractiveness to investors.

-

The licensing round is indicative of the GNU’s effort to develop the country’s oil sector via foreign investment and involvement. This is likely driven by Libya’s inability to significantly increase production by its own resources, where foreign capital and expertise would likely help Libya achieve increased production at a much faster pace. For instance, some estimates claim that Libya requires between three to four billion USD to increase oil production to 1.6 million bpd, highlighting the scale of financing required to get to its goal of two million bpd within the next three years. The fact that the NOC’s entire budget stood at approximately 1.3 billion USD in 2024, highlights the need for external investments to reach its goals.

-

In effect, the new revenue model aims to increase the compensation for the higher risks taken by the IOCs while also retaining the Libyan state’s ultimate control over its oil resources. The new model’s provision for expedited profit-sharing allows the international oil company to recover its costs more quickly, thus increasing the competitiveness of the model. Such incentives may also prompt smaller energy firms to compete in tandem with larger IOCs given the reduced upfront cost of entering the Libyan market.

Politico-Legal Risks

-

At least 17 out of the 22 blocks up for bidding, both offshore and onshore, are located in the Cyrenaica-Sirte basin, which is located largely in LNA-administered territory. Additionally, some of Libya’s key oil export infrastructure, including export terminals such as Brega, Ras Lanuf, and Sidra, are also situated in LNA-administered areas, which indicates that much of the success of the investment campaign lies in the cooperation extended by the LNA.

-

There remains precedent of local groups in production-critical areas forcing operations to stop as a tool to highlight grievances, often tied to socioeconomic demands and occasionally supported by political actors. In April 2022, the NOC declared force majeure at multiple facilities in the LNA-controlled Oil Crescent and Fezzan regions after protesters blocked access, responding to GNU PM Abdel Hamid al-Dbeibah’s refusal to cede power to the LNA-backed GNS. Such incidents are often linked to broader political developments, including confrontations between Libya’s rival governing authorities. Similar disruptions may occur again as a form of political pressure during periods of heightened tension.

-

Despite ongoing political tensions between Libya’s rival authorities, a successful bid could draw significant investment to eastern Libya. However, the GNS and LNA have not issued public statements or clarified their position. This restraint is likely intended to avoid appearing supportive of the GNU’s actions, despite the potential benefits of increased investment, production, and influence in eastern Libya. However, The GNS-LNA-HoR coalition may have deliberately used a technical body, like the HoR-backed Competition and Antitrust Council, to voice objections in a way that appears regulatory rather than political. This approach likely aims to legitimize their criticisms without provoking political backlash or discouraging investment. Furthermore, the GNS-LNA-HoR combine is likely deploying technical objections as a means to exert political pressure on Tripoli and negotiate more favorable concessions in the deal, including greater control over revenue-sharing mechanisms.

-

Despite the lack of serious objections by the GNS-LNA-HoR combine, investors may be skeptical about the prospect of investment given the significant political risk posed primarily by a lack of a unified government with Libya. The need for separate negotiations with two ruling authorities under differing terms, alongside uncertainty over Libya’s governance, is likely to deter long-term investments due to the possibility of the invalidation of contracts and even the possibility of expropriation in the event of leadership changes. Moreover, the absence of a unified government raises concerns about inadequate adjudication mechanisms for commercial disputes, leaving international investors exposed to significant legal risks. These vulnerabilities are further compounded by Libya’s ongoing political instability.

Security Risks

-

At the time of the March 2025 announcement of the new revenue model and bidding round, Libya’s security situation, particularly in Tripolitania, was arguably more stable than during periods of heightened unrest in 2022. The GNU and NOC were likely attempting to frame this relative calm, marked by fewer militia confrontations, the dismantling of armed groups near Tripoli, and tighter control in Zawiyah, as evidence that their territories were ready for renewed investment and operations.

-

However, the security situation in Tripolitania has significantly deteriorated since May 2025, triggered by the killing of Abdul Ghani “Ghneiwa” al-Kikli of the Stabilization Support Apparatus (SSA) by rival militias in Tripoli, which led to infighting between militia groups aligned with the GNU and more independent militias operating in Tripoli. While a ceasefire between militia groups is currently largely in place in Tripoli, tensions between these groups continue to persist as evidenced by two inter-militia clashes that took place on June 9 and August 14.

-

The risk of renewed clashes in Tripoli remains high due to the GNU’s declared intent to dismantle armed groups operating in the city. On July 6, PM Dbeibah described these groups as “a state within a state,” likely referencing independent militias such as the RADA Special Deterrence Forces (SDF). Any effort to weaken or remove these factions will likely face strong resistance, potentially resulting in widespread violence. If militias from surrounding areas intervene, including GNU-aligned forces from Misrata and opposition groups like Osama Juwaili’s Western Mountain Military Region, the conflict could expand across Tripolitania, which in turn can prolong the fighting and expand its geographical scope.

-

Under these circumstances, there remains a significant risk to oil infrastructure across Tripolitania, which is liable to come under attack by anti-GNU groups seeking to undermine the GNU. One such incident occurred on May 28, when social media footage indicated that unknown gunmen stormed the NOC headquarters in Tripoli and allegedly threatened NOC staff regarding “contracts.” In response, GNS Prime Minister Osama Hammad warned of precautionary measures, including possibly declaring force majeure or relocating the NOC headquarters to a “safe” city such as Ras Lanuf or Brega. While the GNU subsequently made arrests related to the NOC incident, the event highlights the vulnerability of the oil sector, given the GNU’s inability to protect Libya’s central oil authority.

-

Additionally, security incidents remain frequent in Zawiyah, approximately 45 km west of Tripoli. In early August, the GNU reportedly launched drone strikes as part of a separate campaign targeting illicit activity, including narcotics and human trafficking. The latest drone strikes are in addition to intermittent inter-militia clashes that continue to affect the city, which is located near the Zawiyah refinery, Libya’s largest functioning refinery.

-

Taken together, these incidents underscore the volatility in Libya’s security environment, particularly in Tripolitania, thereby presenting credible security risks for firms wanting to operate in the region, both through direct attacks on facilities and broader instability affecting investor confidence. Such risks remain high in the coming weeks and months given GNU’s intent to consolidate its security apparatus in Tripoli and beyond, which could provoke a significant backlash among local groups.

Forecasts

-

There remains a possibility of public backlash if segments of the population perceive the deal as disproportionately generous towards IOCs at the expense of local production and may protest against any successful contracts awarded to such companies. Based on precedent in these cases, protesters may choose to express their objections through disruptions in oil operations, including blockades on facilities, valve closures, port obstructions among other disruptive activities. This risk is elevated in the LNA-administered Oil Crescent Region, whose locals, often backed by the LNA, have previously disrupted oil operations through protest activity in January demanding the shifting of Libyan state-owned oil companies headquarters’ to the region. Given that no permanent solution has been determined to such demands, the risk of similar disruptions will likely persist.

-

Without a satisfactory revenue-sharing mechanism, successful bids for blocks in LNA-held territory risk disputes from eastern authorities that could escalate into operational disruptions, including the forced shutdown of oil fields and export terminals in the Oil Crescent by LNA-affiliated militias or organized protest groups. These disruptions are also likely to extend to exploration operations and not necessarily be confined to extraction.

-

Despite the objections raised by the Competition Council, the NOC is likely to continue attracting bids for exploration of the designated blocks, as also exemplified by the MoUs signed with different IOCs so far. Given the lack of an outright objection stated by authorities in eastern Libya, the bidding rounds itself are unlikely to trigger major security events in the country. However, the commencement of exploration or the discovery of extractable resources could serve as a trigger for eastern-based authorities to contest claims with the NOC.

-

IOCs are likely to adopt a wait-and-see approach until there are clearer governance structures and legal assurances, including a formal endorsement by the GNS in eastern Libya. As a result, investment in Libya’s oil and gas may be pushed through pilot projects, particularly in exploration, rather than large capital projects in the coming months.

-

The ongoing security challenges in Tripolitania will likely remain a significantly limiting factor for IOC interest in entering the Libyan oil and gas market. This will likely manifest as delays in opening branch offices in Libya, delayed or postponed travel for prospecting, and higher risk insurance premiums for initiating projects.

SCOUT

INTEL AI BY MAX SECURITY

Fill in your details to schedule a demo with our team.