This report was written by:

Oded Berkowitz – MAX Security’s Associate Director of Intelligence, Middle East & North Africa

And reviewed by:

Tzahi Shraga – MAX Security’s Chief Intelligence Officer, ret. LTC from the Israeli intelligence community

Roshanna Lawrence – MAX Security’s Regional Director of Intelligence, Middle East & North Africa

Executive Summary

Several prominent political actors, supported by various foreign countries, are currently active in Libya in various spheres of influence, some of which overlap. Despite attempts made towards unification including the announcement of a “unity government”, political rifts have deepened in recent weeks. In this context, the political instability of the country is expected to continue, both in a dichotomy of two governments competing for hegemony, as well as in internal rivalries within the various political layers.

Similarly, numerous armed factions operate throughout Libya, some supported by foreign actors (including such that are present on the ground), and hold conflicting or overlapping sets of ideologies and interests with each other. Despite taking measures towards the elimination of militancy, mostly that posed by the Islamic State (IS), the continued political stalemate and deteriorating economic situation, mostly related to the inability to produce and export oil in sufficient quantities, poses a risk of escalation in armed conflict. Overall, a resumption of large scale hostilities between rival armed factions remains possible.

As a result of these factors, the potential for a significant stabilization in Libya over the coming months remains low at this time.

Current Situation

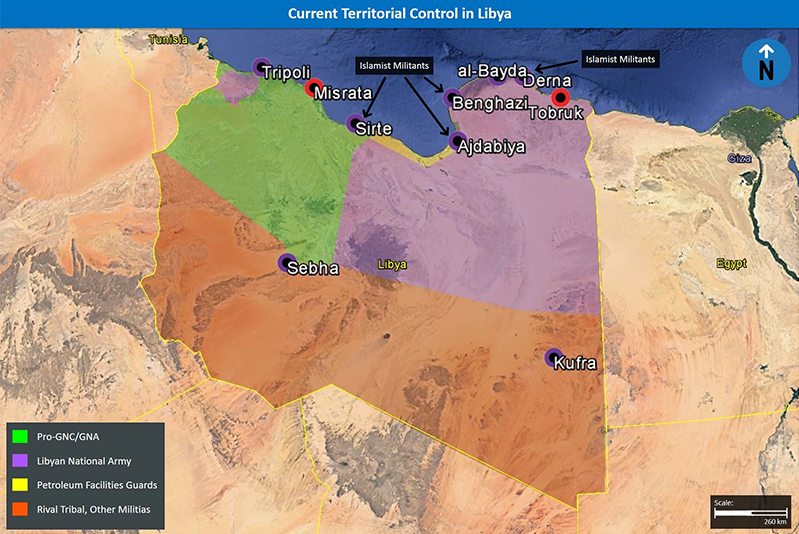

Several prominent political actors, supported by various foreign countries, are currently active in Libya in various spheres of influence, some of which overlap. Despite appearing generally cohesive, there are divided influences and presence of opposing groups not only within the broader geographic areas, but even within certain cities that are seemingly under the control of a certain group. With this in mind, general control of Libya’s major geographic areas can be broken down as follows:

- Eastern Libya: Generally under the control of the House of Representatives (HoR)/Libyan National Army (LNA), with Islamist militant pockets of control.

- Central Libya: Convergence of control by LNA, Petroleum Facility Guards (PFG) and pro-Government of National Accord (GNA)/General National Congress (GNC) forces, with Islamist militant pockets of control.

- Western Libya: Presence of forces that support the GNA and others that support the GNC, with a pocket of LNA control.

- Southern Libya: Generally ungoverned territory with heavy presence of tribal militias who hold shifting alliances.

See below, “Actors and Interests”, for a more in-depth discussion of the major players.

Forecast: Militancy and Fighting

Eastern Libya: Status quo likely to continue

- Despite its unprecedented recent successes, the LNA has suffered some local setbacks, namely the inability to hold areas that it “liberated” in Ajdabiya in March-April, as is manifested by the renewed militant territorial presence and operational capabilities in and around the city. These are likely the result of the LNA’s need to engage in several active fronts that are also physically distant from each other at the same time, thus forcing the LNA to overstretch its resources. Moreover, the LNA’s airpower, one of its main leverages, is inconsistent in its operations due to faulty maintenance (as a result of lack of proper resources) and overuse. Moreover, in Benghazi, the primary area of operations for the LNA currently, the LNA faces persistent challenges in operating in a dense urban area and among civilians, a weakness often successfully exploited by militant groups that battle the LNA.

- Lastly, the recent exposure of the French military presence in Libya prompted widespread local opposition, mainly from (but not exclusive to) civilians in Misrata and Tripoli, as well as the Grand Mufti, and is expected to cause opposition from the local population, as well as political complications. In the long term, that may mean that France will have to scale back its missions in Libya, or possibly entirely withdraw from the country, which will have particularly adverse effect on the LNA, France’s main beneficiary in Libya. These factors combined will likely result in a general status-quo of fighting in the east in the coming period, with the LNA making advances in certain areas, however at the expense of losing grounds or influence in other areas.

Central Libya: Misrata forces likely to eventually seize control of Sirte; factional fighting possible over coming months

- As opposed to the east, in the Sirte Basin, pro-GNA forces (mostly in the form of militia groups from Misrata) were largely not required to fight in several different, far-removed focal points. As a result of this, along with an at least temporary alliance struck with the PFG in the east of the basin, pro-GNA forces were therefore able to focus their forces to the maximum effect against IS and achieve far-reaching results. Given that IS’s main fighting forces have mostly been contained to a small area, which is besieged from all sides, we do not assess that it currently has the capabilities to break the encirclement and reverse Misrata’s achievements. The latter will likely opt to generally maintain the siege for the coming period in order to avoid high casualty tolls that are attributed to fighting in urban terrain, and will likely mostly bombard the city with air and artillery forces. With this in mind, unless something unexpected – such as premature renewed fighting with the LNA or PFG occurs, we assess that Misrata’s capabilities in ultimately capturing Sirte will remain high.

- However, it is important to mention that while IS’s capturing and expansion of territory in the Sirte Basin since February 2015 served to temporarily mitigate hostilities between the LNA and the then-Libya Dawn, whose main focal point of fighting prior was the control over oil facilities in the Sirte Basin, and mainly the oil terminals along the coast. In this context, the eventual removal of IS as a major threat may in fact reignite fighting (depending also on the political situation at the time) between the LNA, Misrata, and the PFG over the control of the numerous valuable energy resources in the area.

- Indications of this were already apparent in early May, when forces from Misrata and the LNA, maneuvering to positions prior to launching an offensive against IS, briefly but intensely clashed with each other near Zillah and its nearby oil fields. This is particularly likely since oil and gas, which are abundant in the Sirte Basin, are Libya’s main exports, even at the significantly reduced current output, and are therefore a key factor of income, thus rendering the control of energy facilities instrumental for any actor seeking influence in Libya.

Western Libya: Outbreak of fighting between rival militias possible over coming months

- Despite the GNA’s arrival in Tripoli and the subsequent large support base they were able to rally among local militia, the fractioned nature of the “military” structure in the west, which also characterized the previous Libya Dawn coalition of militia forces, persists. This results in occasional, intense, fighting between militia groups both in Tripoli and its surrounding areas, including between those that seemingly operate under the same group, over a variety of issues including control and patronage of areas, dominance over smuggling routes, as well as over local disputes, in addition to fighting that occurs between militias of rival political affiliation, namely the GNA and GNC loyalists. This situation is underscored by the most recent fighting in Garaboulli, 60 km east of Tripoli, on June and 21 which resulted in at least 29 deaths and dozens of wounded.

- Moreover, fighting intermittently occurs between militia groups that support the LNA and the HoR, and those that support the rival factions, along the “border” west and southwest of Tripoli. The presence of pro-LNA forces in such relatively close proximity to Tripoli, in addition to the fragility of the political situation, runs the risk of an expansion in hostilities over the coming six months, particularly since multiple LNA commanders have announced in the past that their “ultimate goal is Tripoli”. This risks will be significantly heightened should hostilities between the LNA and pro-GNA forces in the Sirte Basin be resumed, potentially resulting in a spiral effect that will renew a nationwide state of hostilities such as the one that was prevalent in Libya approximately one year ago.

Countrywide Militancy: IS losses may lead to more high-profile attacks by group, while regional competition with AQIM may lead latter to exploit such losses

- Despite the proliferation of militant groups in Libya, these organizations are mostly invested in maintaining their activity around their current areas of operations, namely in and around Derna, Benghazi and Ajdabiya. An exception to these is IS, who has both the interest and the proven capabilities to operate across Libya, and has in fact conducted attacks across the country in recent months. While IS’s loss of territory, material, and personnel first in Sabratha (west of Tripoli) in March, then in Derna in April, and finally in the Sirte Basin since June, has significantly impaired their resources base and operational capabilities, this exact same process may lead the group to conducting more high-profile attacks. This is in order to maintain the group’s diminishing prestige and project an image that it is still relevant despite its losses, both regionally and globally, due to its setbacks in Libya, as well as in Syria and Iraq.

- Moreover, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), who is a regional competitor of IS and draws from similar recruitment and funding pools, also has an operational presence in the country and may seek to take advantage of IS’s current setback to increase their own influence in the country, which will be manifested by militant attacks. In this context, while the frequency of militant attacks has declined in recent weeks, in the long term, the increased motivation and remaining capabilities of the numerous militant factions serve as indications that attacks may occur nonetheless. In light of precedent and the global jihadi groups’ strategies, such attacks are likely to prioritize strategic locales such as the energy sector (as noted before), as well as foreign companies and diplomatic missions, to further damage the economy, aggravate the instability of the state, and capitalize on the resultant void that allows militants to prosper.

Forecast: Political Stability

Political competition likely to persist between rival governments, increasing fractured nature of country

- Since its arrival in Tripoli, the Presidency Council of the GNA has successfully expanded their sphere of influence in western Libya. That said, their influence was generally unsuccessful in breaching into the east of the country, which is still mostly under the auspices of the HoR. Furthermore, there is a common perception by locals of the GNA as being foreign installed and directed, which was likely aggravated by the “invitation” of US airstrikes and foreign intervention in Libya. This image significantly impairs the GNA’s domestic credibility, despite being presented as the unity government of Libya.

- The rift between the GNA and HoR is aggravated by the continued inability of the HoR to hold a vote to ratify the GNA, which is perceived by the latter as an intentional move to diminish its legitimacy. Additionally, the fact that the GNA continues its own implementation despite not being vetted by the HoR is perceived by the latter as an act of marginalization of the body, which is set to be the legislative authority of the unity government. Most recently, political rivalries peaked when, following an agreement in late July between the GNA and PFG to reopen the major oil terminals in central Libya in late July, the HoR threatened to attack vessels entering Libyan territorial waters without the latter’s authorization.

- In this context, the HoR will likely continue to fail meeting voting deadlines on the ratification of the GNA, as it postpones the latter’s full implementation without outright rejecting it. This, in turn, blocks what some of the HoR members perceive as a challenge to their aspirations of sovereignty, without attracting the negative international attention and potential ramifications that will accompany an official vote against what at least the UN perceives as a unity government. Should this process persist, it is liable to prompt the Presidency Council to continue to construct the GNA without ratification, which in turn will further discredit its domestic status and sanction political opposition to it. This will likely eventually lead to the GNA establishing their primacy in the west, but remaining a second government in Tripoli and western Libya vis-a-vis the HoR, mostly in the east.

- That being said, it cannot be ruled out that the HoR will eventually ratify the GNA. However, even without the political branch’s dichotomy, Libya’s institutions, and more importantly its various fighting groups, still hold many conflicting interests and ideologies, along with personal animosities between leaders of these groups, which will significantly challenge the implementation of a full unification of Libya. Taken as a whole, the most stabilizing potential outcome for Libya, and the one that seems least likely at the time of writing, will see a single domestically and internationally recognized government which struggles to exert its full control over Libya, in which various competing groups will still clash with each other to maintain their respective interests. However the most likely track at this time, which will maintain and possibly exacerbate Libya’s instability, is one in which the GNA continues to compete with the HoR, and to a lesser degree with the GNC, over full control of Libya, in effect resulting in a fractured state.

Actors and Interests

Political Actors

- Government of National Accord (GNA): Currently based at the Tripoli Naval Base, the GNA is intended to be a unity government and is a product of the Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) signed in December 2015. The LPA allows for the transition of the House of Representatives (HoR) and General National Congress (GNC) into the GNA’s legislative body and advisory State Council, respectively. However, this transition must be ratified of a vote of a special majority by the HoR, which so far has not been able to convene the needed quorum for such a vote. During this continued transition period, the GNA is currently considered the “internationally recognized” government and enjoys the support and the backing of the UN. Its sphere of influence is fractioned mainly throughout western Libya, particularly in greater Tripoli and Misrata.

- House of Representatives (HoR): The previously “internationally recognized” government, the HoR’s parliament is based in Tobruk and executive branch in al-Bayda. Its sphere of influence is generally in eastern Libya, with some pockets of support in the west, particularly southwest of Tripoli. The HoR is currently supported politically, militarily, and economically by several countries, most prominent the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt. While these countries generally recognize and support the LPA, they capitalize on the fact that the HoR has not ratified the agreement as pretext to consider it non-valid at this time, in order to continue supporting the HoR and not the GNA.

- General National Congress (GNC): The GNC previously controlled the majority of western Libya and is now mostly defunct, mainly since some of its members unilaterally broke away in early April and started fulfilling the role of the State Council, despite the GNC leadership’s opposition. While the GNC currently has very little political power, it still enjoys support from various militias, as well as from Grand Mufti al-Ghariani, thus retaining a partial sphere of influence in the west, particularly in Tripoli and its surrounding areas. Both Turkey and Qatar originally supported the GNC, but this support has diminished since the start of the GNA’s implementation.

- Other groups: Both the ungoverned and the governed areas of Libya are dominated by politics based on tribal, clan, and ethnic backgrounds, as well as place of residence and origin. In this sense, it is not uncommon for cities that both support the same political body, to be at odds due to historical or other rivalries among their residents. Similarly, militias from the same city who support the same political organ may have a strife over tribal or other rivalries.

Militia and Militant Groups

Dozens of militia and militant groups currently operate in Libya, each with its own ideologies, interests, and political allegiances. Very broadly, these groups are categorized into six different competing factions, with rivalries persisting even within some.

- Militia groups that support the Libyan National Army (LNA), which is commanded by Lieutenant General Khalifa Haftar and holds patronage relations with the anti-Islamist House of Representatives (HoR). Mainly fighting in the east of the country, with pockets of support in the west. Their main areas of operations currently are around the city of Derna, in Benghazi, in and around Ajdabiya, as well as the area between Benghazi and Ajdabiya.

- Militia groups supporting the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA), based at Tripoli Naval Base. Currently engaged in an ongoing campaign to remove the Islamic State (IS) from the city of Sirte (represented primarily by forces from Misrata), as well as taking part in intermittent inter-militia fighting in western Libya.

- Militia groups, formerly known as the Libya Dawn coalition, supporting the pro-Islamist General National Congress (GNC), based in Tripoli. While mostly defunct, they still retain some fighting capabilities which are mostly invested in fighting rival militias, mainly those that support the GNA, in Tripoli and other areas in western Libya.

- Petroleum Facility Guards (PFG), an independent faction that holds shifting alliances (currently allied with pro-GNA forces), however ultimately strives for its own goal of a federalist Libya. Currently is seldom fighting and mostly retaining its forces. Was briefly involved in operations against IS east of Sirte in cooperation with Misrata.

- Islamist jihadist groups such as the Islamic State (IS), as well as additional ones that hold varying levels of connections to al-Qaeda, the GNC and/or the Grand Mufti of LibyaSadeq al-Ghariani, including Ansar al-Sharia, Revolutionary Shura Council of Benghazi (RSCB), Mujahideen Shura Council of Derna (MSCD), and others. Hold territory and operational capabilities mainly in and around Derna, Benghazi, Ajdabiya and Sirte.

- Tribal militias, mostly consisting of either Tebu or Tuareg ethnic tribes, who may be at times supported by fellow tribesman from neighboring countries, and hold shifting allegiances towards the various players. Operate mainly in the ungoverned territories in southern Libya, in proximity to the border with Egypt, Sudan, Chad, Niger and Algeria.

International Actors (Non-Regional)

Numerous international actors have either confirmed their military presence on the ground in Libya in support of either of the factions, or have indications pointing to such activity by them without official confirmation at this time. This is in addition to indirect actions such as the ongoing Operation Sophia to counter illegal immigration, an actions by regional actors such as Egypt, UAE, Turkey and Qatar which will be mentioned in the political stability section. The main international actors are:

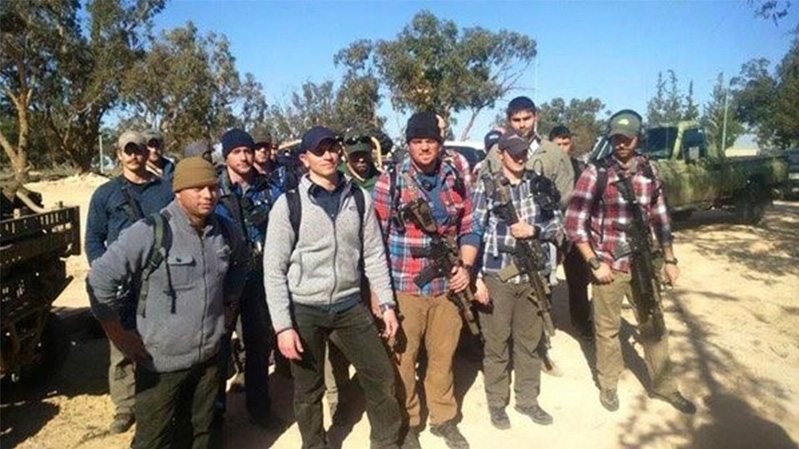

- The United States: On July 19, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford confirmed that the US has routine and ongoing operations in Libya that are coordinated with the GNA, as well as other operations that are not coordinated with them, without specifying their nature. Later, on August 1, the US Department of Defense (DoD) announced that US aircraft targeted IS positions in Sirte on August 1, at the request of GNA leadership. In addition, the DoD stated that further airstrikes targeting IS in Sirte would be conducted in support of “GNA ground operations”. There are many indications of US ground and aerial operations in areas both under GNA (and previously GNC) control as well as in HoR territory. The most prominent evidence of US ground presence in Libya emerged as early as December 16, 2015, when a Special Operation Forces (SOF) team sent to advise the LNA was expelled from al-Watiyah Airbase by local militias, compelling the DoD to confirm that the US military is dispatching “advisors” toLibya.

- Italy: Provides frequent and overt logistical support primarily to the city of Misrata, most often in the form of medical evacuation of both civilians and combatants wounded by IS actions. There are local reports of regular presence of Italian SOF teams providing training, advising and liaison with locals, however these remain unconfirmed at the time of writing.

- France: On July 17, an Islamist militant group claimed to have shot down an LNA helicopter carrying Libyan, French and Jordanian nationals. While there are conflictingreports regarding the type of helicopter and the reasons for which it crashed, on July 20 French President Francois Hollande confirmed that three French operators were present aboard a helicopter that crashed due to technical reasons in Libya; reports additionally indicate that the three were Directorate-General for External Security (DGSE) agents. This announcement accounts for the first official and public admission of direct French operations in Libya, while local reports regarding relatively large scale French presence and operations in Benghazi circulated since February.

- United Kingdom: There are various local reports regarding direct British involvement in assisting Misrata forces in their campaign against IS in Sirte. While unconfirmed reports suggest that UK forces directly engaged IS forces in certain instances during May-June, both on the ground and with use of airstrikes, Misrata’s military spokesmen stated that the UK is only providing intelligence support, including by operating tactical unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), as well as in advising local forces.

- Russia: On May 1, the LNA’s official spokesman announced that the LNA’s operations are assisted by Egypt, the UAE and Russia. This accounted for the first official recognition of Russian involvement in Libya. While there is little open source information regarding potential Russian operations in Libya, on January 31, a Russian Orlan-10 tactical UAV crashed near Ajdabiya, an incident that remained unexplained since and may serve as an indication for such ground operations.

DISCLAIMER: Please note that any views and/or opinions and/or assessment and/or recommendations presented in this text are solely those of Max Security. If you are not the named addressee you should not disseminate, distribute or copy this text. If you are not the intended recipient you are notified that disclosing, copying, distributing or taking any action in reliance on the contents of this information is strictly prohibited. Max Security Solutions accepts no liability for (i) the contents of this text/report being correct, complete or up to date; (ii) consequences of any actions taken or not taken as a result and/or on the basis of such contents. Copyright – 2016 Max Security

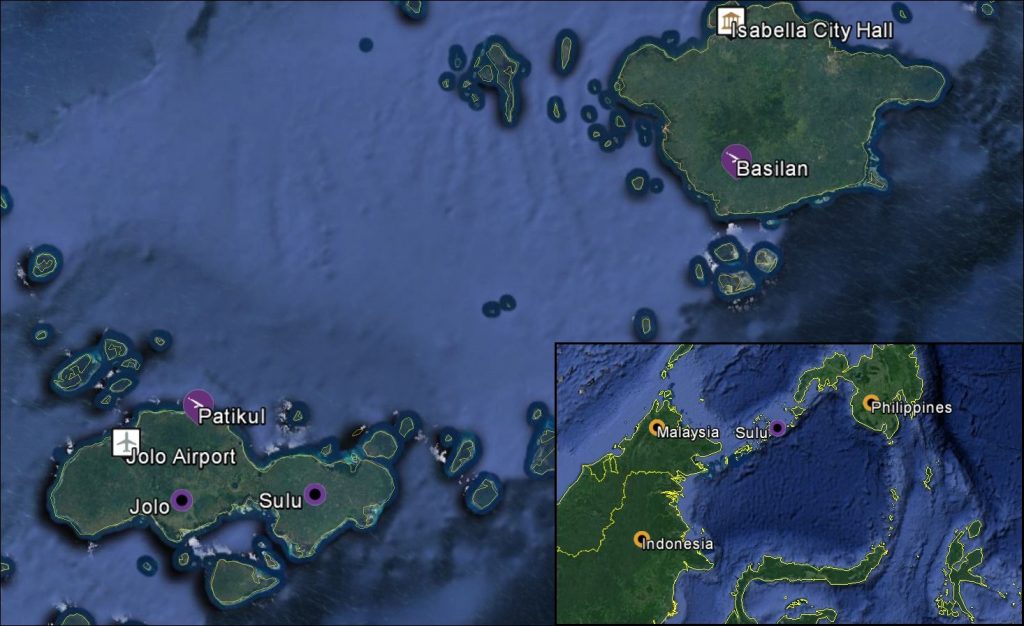

Focal points in Sulu Archipelago

Focal points in Sulu Archipelago

Original claim taken from Islamic State media

Original claim taken from Islamic State media