Current Situation

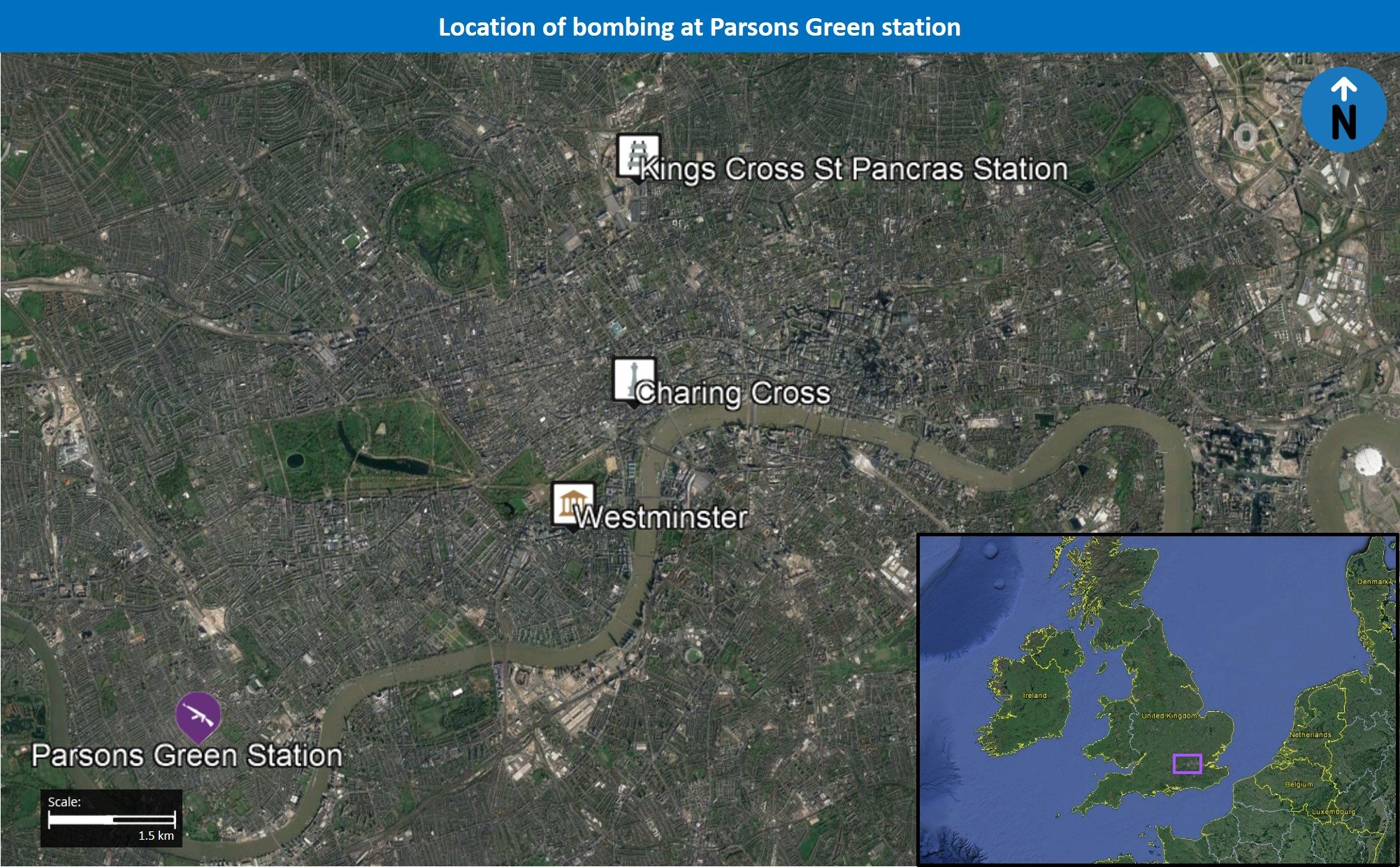

During the morning hours of September 15 a small explosion occurred in the carriage of a District Line London Underground Train at Parsons Green Station in West London, which left around 30 individuals injured. The explosion was reported as causing a “fireball” in the rear carriage of the full rush hour train, which traveled down the carriage leading to a number of flash burns on commuters. None of the injuries were classified as severe, however, at least 19 of those affected were taken to hospital in ambulances.

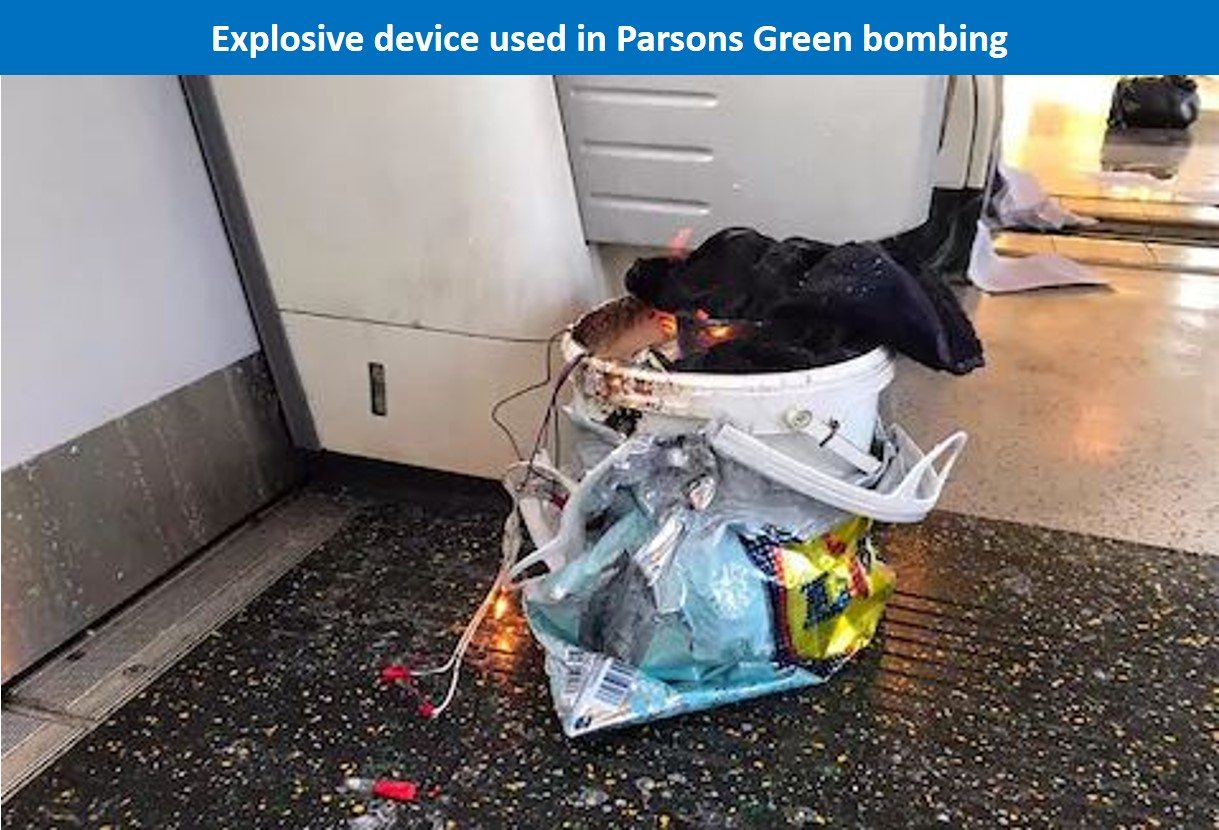

According to reports, the IED-device appeared to have been packed in a plastic bucket covered by a supermarket bag and strategically placed inside the crowded tube train to maximize casualties. Investigators believe that the device was possibly designed to be remotely detonated suggesting that it was not intended to be a suicide attack. The device was filled with triacetone triperoxide (TATP) an explosive which can be fairly easily created from available elements, which has been common in IS claimed attacks. Bomb disposal experts have said that the initiating charge of the explosive had exploded upon triggering but the device failed to detonate the main charge making the attack less destructive than expected. According to reports, the explosive was placed onto the train and the militant left the train before it detonated.

On September 15, the Islamic State (IS) published a statement through social media outlets claiming responsibility for the IED explosion. According to the statement, multiple explosive devices were planted, of which one detonated at Parsons Green Station. It further threatened that future attacks will be “more devastating and bitter”.

Prime Minister Theresa May raised the militant threat level following the incidents on September 15 to ‘critical’, the most severe level in the country’s threat scale. Additionally, May said that military personnel will replace police officers on guard duties at specific protected sites which are not accessible to the public. Meanwhile, armed police forces are set to be deployed on the transport network and on streets to provide extra protection.

On September 17, the UK terror threat level was reduced from critical to severe (the highest to the second highest), after two arrests were made in connection with the bombing. One 21-year-old was arrested in Hounslow, West London, during the night of September 16 on suspicion of militancy and is in custody in South London. An 18-year-old man is also being held on suspicion of militancy over the Parsons Green explosion.

Background

Triacetone triperoxide or TATP has a long history of being used in improvised explosive devices (IEDs), particularly by Islamist militants. The explosive has a number of properties which render it preferable for carrying out acts of militancy, particularly for less connected or well-trained operatives. First of all, TATP can be created with relatively low cost and ease as all of the ingredients needed to create the compound can be obtained legally in any major city. Second of all, TATP is one of the few explosives that does not contain nitrogen, meaning it can pass through explosive detection scanners designed to detect nitrogenous explosives without raising alarm. The downside, however, of TATP is that it is highly volatile and prone to “workplace accidents” in bomb-making factories, a property which earned it the name “Mother of Satan.”

The most notable use of TATP in terms of Islamist militancy in the UK was during the 7/7 bombings in London in 2005, which killed 52 people and injured as many as 700. However, in recent times, the Islamic State has called for followers to use TATP, due to the many advantages mentioned above, in carrying out bombings in Europe. Particularly the explosive substance was employed in the November 2015 Paris attacks and 2016 Brussels bombings. More recently the explosives were used both in the Manchester Arena bombing and were the principal component in causing the explosion which preceded the August 2017 attacks in Catalonia.

Assessments & Forecast:

Failure of IED indicates lack of expertise on part of perpetrators, likely carried out by IS-inspired lone wolf/homegrown cell

There are two primary reasons as to why the explosive device failed to detonate properly and that the attack was not carried out to its full potential. The first is that the explosion which was recorded was far smaller than what one could expect from the size of a TATP based IED, in addition to reports that the detonator was unable to ignite the explosive material, causing a diminished blast.

In this context, the fact that the device failed to detonate properly is notable in that the seemingly poor assembly of the IED may be indicative of the bomb not being put together by an individual with a great deal of expertise in the field of explosives. On the contrary, it indicates the possibility that the device was assembled by a militant who is relatively inexperienced with building explosives and likely was following instructions found in an online manual. This assessment is bolstered by the fact that a number of IS publications and online messages have noted the TATP explosive as a preferred methods for their followers to carry out attacks.

With this in mind, we assess that the perpetrator or perpetrators of the Parsons Green attack were likely domestically radicalized individuals who were inspired by the Islamic State, but may not have had any direct or active connection with the group. The incidents can be seen as part of the continuing trend of attacks being attributed to lone wolf militants and “homegrown cells”, which are later claimed by the Islamic State, despite typically not being oredered by the group’s central command in the Middle East. This model has been increasingly the case for attacks in Europe, the majority of which have been carried out by individuals and groups who had not traveled to the Middle East, but rather were radicalized domestically, and used the propaganda from IS on online messaging forums and online magazines to take inspiration for targets and methods.

Failed large bombing in London indicates growing trend in attempted spectacular attacks by homegrown cells across Europe; likely to see further major bombings going forward

While the device which exploded did fail to reach its full destructive potential, had the attack been carried out successfully the incident could have been one of the most destructive militant attacks seen in the UK in recent times, and a notably spectacular one in terms of European militant jihad. The notoriety and spectacularity of the attack would also have increased had the attack been carried out in a larger, more famous station as may have been the plan. With this in mind, the incident appears to come as part of a trend in Europe of IS-inspired militants looking to carry out bigger, more destructive, and more spectacular attacks in major cities. While there have been large attacks carried out in Europe, such as the 2015 Paris and 2016 Brussels, these were largely carried out and facilitated by returning fighters with strong IS connections in Syria. What stands out about the Manchester Arena attack, the failed Barcelona attack, and the Parsons Green attack, is that these appear to have been orchestrated by domestically radicalized “homegrown cells” with little involvement of returning fighters or IS central command. While the idea of lone wolf attacks has been common in Europe over the past years, they have traditionally involved far less sophisticated attack methods, such as stabbings, shootings, and car rammings.

Keeping in mind the apparent trend that the Parsons Green attack fits into, we assess that there is currently an ongoing shift in the goals of radical Islamists in Europe and their goals with regards to carrying out jihad on the continent. The evolution of jihad in Europe has reached a new development, whereby, through online messaging and propaganda, domestic militants are looking to move away from the smaller low-impact attacks which characterized much of the incidents in late 2016 and early 2017, and move towards more destructive and shocking attacks. Despite the fact that the majority of these unaffiliated radicals do not likely have the same access to the networks available to the Paris and Brussels attackers, nor have the same level of experience, they will nonetheless look to use what means are available to them to create homemade bombs and plan their targets in an attempt to cause the maximum damage and fear.

FORECAST: Such trends in jihad are also self-compounding; the more that smaller cells and lone wolves see other groups carrying out these attacks, the more they are inspired to also conduct similar operations. This is especially the case as each cell attempts to carry out the biggest and most notorious attack, in competition with previous ones and other cells. With this in mind, we assess that further reports of attempted and successful bombing attacks will be recorded throughout Western Europe over the coming weeks and months as many different cells and lone wolves look to take part in the new trend of larger bomb attacks, to be a part of highly destructive and infamous incidents. These attacks will also likely look towards sites that are considered of particular importance to the continent, such as major tourist hotspots, concert venues, nightclubs, or transport hubs. Moreover, as security forces increase their presence on particular areas (such as the Underground in London), the militants will look to find new vulnerabilities where attacks can be carried out such as on busses.

Escape of perpetrator indicates new threat in terms of European jihad as prior attacks usually involved suicide plans

Finally, it is notable that the attacker did attempt to escape from the bombing and did not plan to martyr himself during the attack. In that vast majority of attacks carried out the militants have traditionally looked to either deliberately kill themselves in the course of the attack or have carried out the attack in such a way that the possibility of escaping was not available. However, the Parsons Green attacker appears to have deliberately attempted to escape the blast and even evade security forces.

Such a method of attack constitutes a new threat within the European theatre, whereby militants may look to increasingly use similar tactics of dropping explosive devices in crowded areas and attempting to escape. Such methods have substantial implications for both security and public order going forward. While there have already been frequent evacuations of central areas and transport hubs in across Europe since the beginning of the IS militancy crisis on the continent, if fears among both security forces and the public increase, with regards to suspicious packages, there are likely to be more disruptions to transport, as well as, in central areas. Additionally, the panic that is caused by such instances has the potential to cause increased injuries and disruptions as stampedes are liable to occur in areas that are being evacuated.

Recommendations

Travel to the United Kingdom can continue while maintaining vigilance to the elevated threat of militancy throughout the country, particularly in major cities and busy population centers.We advise practicing situational awareness for indicators of militant threats such as suspicious looking individuals or packages. In the event that such threat is identified, it is advised to evacuate the area and notify security forces in a calm and timely fashion.

During times when the threat level for militancy in any country or area has risen to its highest level, we advise travelers to minimize nonessential travel to crowded public spaces such as transport hubs, entertainment venues, and well-known tourist destinations.