Current Situation

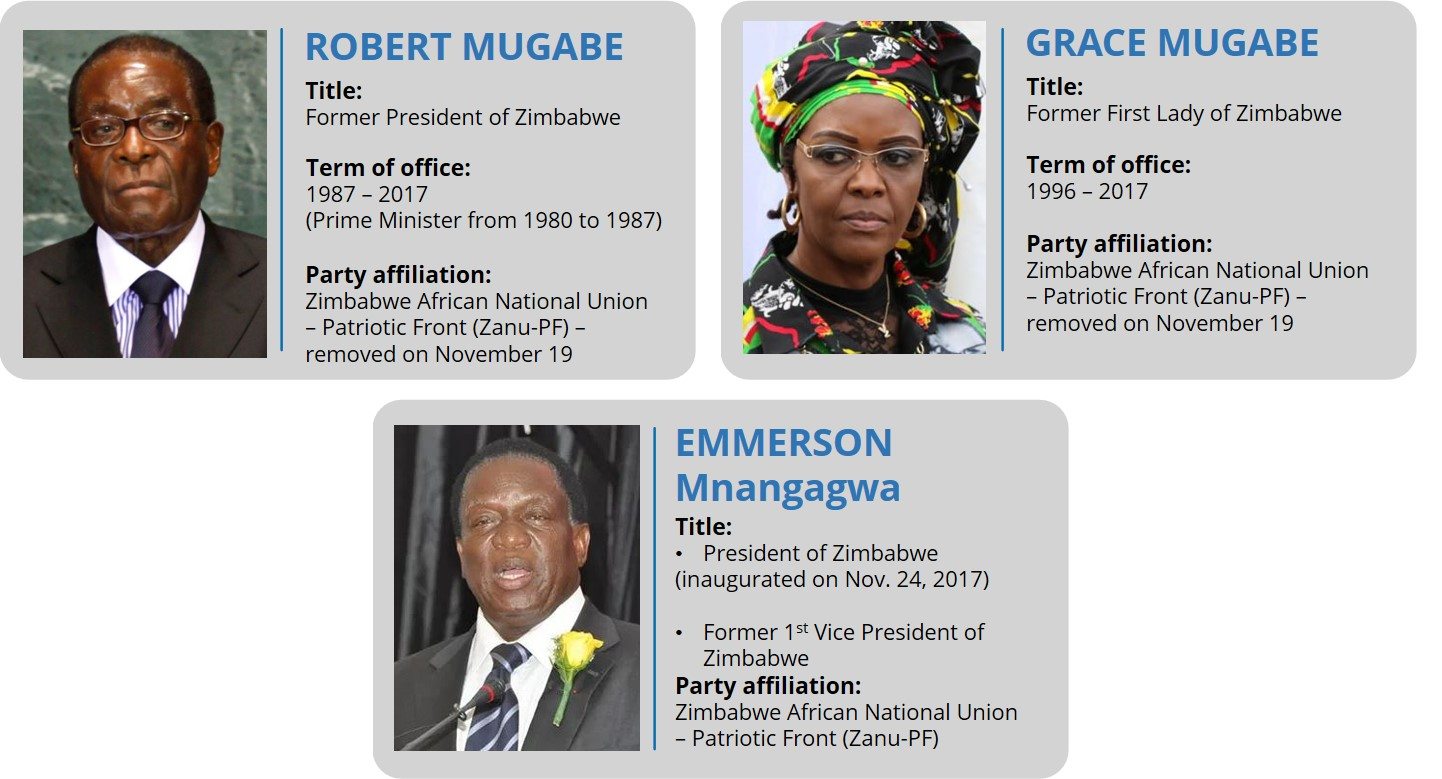

On November 24, Emmerson Mnangagwa was sworn in as Zimbabwe’s president following the resignation of his predecessor, Robert Mugabe, amid a special parliamentary session set to discuss Mugabe’s impeachment on November 21.

Mugabe’s resignations came nearly one week after Zimbabwe’s military took control of the country on November 15, confining President Robert Mugabe and his family to their residence, deploying troops to Harare, and cordoning off key government buildings.

The military intervention came in the wake of a high-profile purge of cabinet ministers and officials of the ruling Zanu-PF party deemed a threat to President Mugabe and his positioning of his wife, Grace, as his possible successor.

Meanwhile, the influential Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans’ Association (ZNLWVA), which had severed ties with the Zanu-PF days before the coup over the expulsion of liberation war veterans from the party, called on Mugabe to resign from the presidency.

In tandem, tens of thousands took to the streets of Harare on November 18 to peacefully protest in support of the army and against President Mugabe’s rule following a call from ZNLWVA’s chairman, Chris Mutsvangwa. Peaceful demonstration continued during the following days.

In light of President Mugabe’s persistent refusal to step down, the Zanu-PF expelled him and Grace Mugabe from the party on November 19, during which they also called on the deposed president to resign by November 21 or face impeachment proceedings. President Mugabe would ultimately ignore the resignation deadline imposed by the Zanu-PF, triggering the the initiation of the impeachment process in the early evening hours of November 21.

Assessments & Forecast

The removal of Robert Mugabe as President of Zimbabwe is the culmination of an internal struggle over his succession. In the first instance, these divisions came to a head over Grace Mugabe’s ambitions to succeed her husband as President of Zimbabwe. She enjoyed the support of the influential Generation 40 (G40) bloc of Zanu-PF, and steps taken by her supporters within the party and President Mugabe to position her as the president’s successor would ultimately exacerbate existing divisions within the party. Notably, Mugabe’s marginalization of Emmerson Mnangagwa, first by way of his removal as Zimbabwe’s justice minister in October and finally as vice president, served to aggravate those inter-party tensions. Mnangagwa’s influence within the party bred suspicion among the pro-Mugabe faction and especially gave the Mugabes themselves pause. Despite enjoying the support of certain powerful Zanu-PF officials, Grace Mugabe was an unpopular, and therefore weak, choice to succeed her husband, making her vulnerable to a challenger from within the party like Mnangagwa, who was widely respected within the Zanu-PF, the military, and the powerful ZNLWVA for his record as a war veteran and as a high-ranking Mugabe deputy dating back to the 1980s.

The Zanu-PF purges that triggered the ZDF intervention on November 15 that would culminate in Robert Mugabe’s removal as President of Zimbabwe arose from these divisions within the country’s ruling party. Not only did these expulsions deepened divisions between the G40 and the pro-Mnangagwa “Lacoste faction”, they also placed both the military and the ZNLWVA, two of the country’s most powerful institutions, firmly on the side of Mugabe’s opponents within the Zanu-PF. As such, the expulsions directly set in motion the events that would end with Mugabe’s resignation. While prevailing social, political, and economic conditions in Zimbabwe were likely responsible for the relative lack of resistance from the Zimbabwean public to Mugabe’s removal, as the ZDF and the ZNLWVA are revered in Zimbabwe as embodying political legitimacy, their support of Mnangagwa was instrumental in Mugabe’s ouster.

As Mnangagwa takes Mugabe’s place as Zimbabwe’s president, it bears noting that while the country will experience its first change of leadership in 37 years, the power dynamics that underpin Zimbabwe’s politics remain effectively unchanged by the events of recent weeks. As previously noted, Mugabe’s removal was fundamentally the result of an internal struggle within the ruling Zanu-PF. Opposition parties never played a major role in the push to depose him, nor did those leading the effort ever seek the opposition’s participation. It is equally crucial to note Mnangagwa’s own role in suppressing political opposition to Mugabe from his early days in the administration. Mnangagwa’s hardline stance against political dissent was most recently evident by his alleged role in manipulating the second round of Zimbabwe’s 2008 elections, following a Mugabe loss in the first round, by reportedly initiating a campaign of violence against opposition supporters and ballot rigging. This developments would ultimately make him, a number of other powerful Mugabe loyalists, and Mugabe himself the targets of international sanctions. In light of this precedent, looking ahead, Mnangagwa is unlikely to promote a new political culture that is more inclusive of Zimbabwe’s opposition parties and their supporters.

Almost immediately after the announcement of Mugabe’s resignation, large-scale public celebrations broke out in Harare and a number of urban centers throughout Zimbabwe, highlighting the event’s significance as a cathartic moment for many Zimbabweans. A key challenge for Mnangagwa in the early days of his presidency will be to manage the public perception of his administration as representing a shift away from the political order designed by Mugabe while continuing to advance the Zanu-PF’s objectives. It is likely that many Zimbabweans who see Mnangagwa’s assumption of power as an opportunity for true change will expect to see that change manifest, first and foremost, in the form of a freer, more open, and more democratic political process.

FORECAST: However, Mnangagwa is unlikely to jeopardize the ruling party’s political hegemony by subjecting it to such a process. He might liberalize Zimbabwe’s press to allow opposition parties and their leaders greater freedom to promote their agendas in an effort to create the appearance of a freer society and to validate the above feeling of catharsis. Additionally, as witnessed in 2008, Mnangagwa might invite opposition parties such as the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) to take part in the interim government, nonetheless, their eventual involvement is expected to be superficial, as substantial changes remain unlikely.

In the first months of his presidency, Mnangagwa will likely attempt to foster continued public support of his presidency. In this context, the country’s flagging economy is perhaps the area of greatest concern for the Zimbabwean people as the country remains in the throes of a long-term economic and financial crisis, which has seen the purchasing power of the country’s citizens disintegrate and the value its currency, dwindle.

FORECAST: Accordingly, Mnangagwa will likely seek to prioritize economic renewal as a means of shoring up support for his presidency and the Zanu-PF leading up to the 2018 elections, first and foremost by initiating new appeals for economic aid from international donors, namely western powers, as well as various international financial institutions. Recent precedent in other parts of Africa, most notably in Rwanda under long-serving President Paul Kagame, has demonstrated the effectiveness of economic revival as a means for a head of state to rally support for his government after a long period of economic hardship, even if at the expense of promoting democracy. Thus, Mnangagwa can be expected to prioritize economic recovery in the early months of his presidency and likely up to next year’s elections until he has secured his next term of office.

However, Mnangagwa’s success in reviving Zimbabwe’s economy will be limited, at best, without the support of the international community. The governments and institutions best positioned to provide Zimbabwe with economic aid are unlikely to do so if they perceive the new Mnangagwa government as a simple continuation of the Mugabe administration. Indeed, foreign governments previously imposed economic sanctions against the Zimbabwean government and many of its officials under Mugabe, including Mugabe himself, and have extended them as recently as January 2017.

FORECAST: The indispensability of international assistance to Zimbabwe’s economic recovery over the coming months represents the strongest incentive for Mnangagwa to promote democracy and pluralism in Zimbabwe, even if only superficially. Accordingly, it is likely that Zimbabwe’s 2018 general elections will continue as planned, likely under the supervision of international election observers from start to finish as precondition for economic aid.

Recommendations

Travel to Harare and Bulawayo can continue while adhering to basic security precautions against common criminality.

For any further questions or consultation, please contact us at [email protected] or +44 203 540 0434.