Executive Summary

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) emir Abdelmalek Droukdel was killed by French forces in Mali, a significant symbolic loss that will likely exacerbate the ongoing decline in al-Qaeda operations in Algeria and Tunisia.

This will likely result in the continued diversion of resources and focus to the Sahel, reducing the operational support given to Algerian and Tunisian groups as well as diminishing morale and recruitment in the Maghreb.

The impact on al-Qaeda in the Sahel will likely be limited given the decentralized nature of AQIM’s control and the broader success of Malian leaders of the other constituent groups within the al-Qaeda coalition in the Sahel, Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam waal Muslimeen (JNIM).

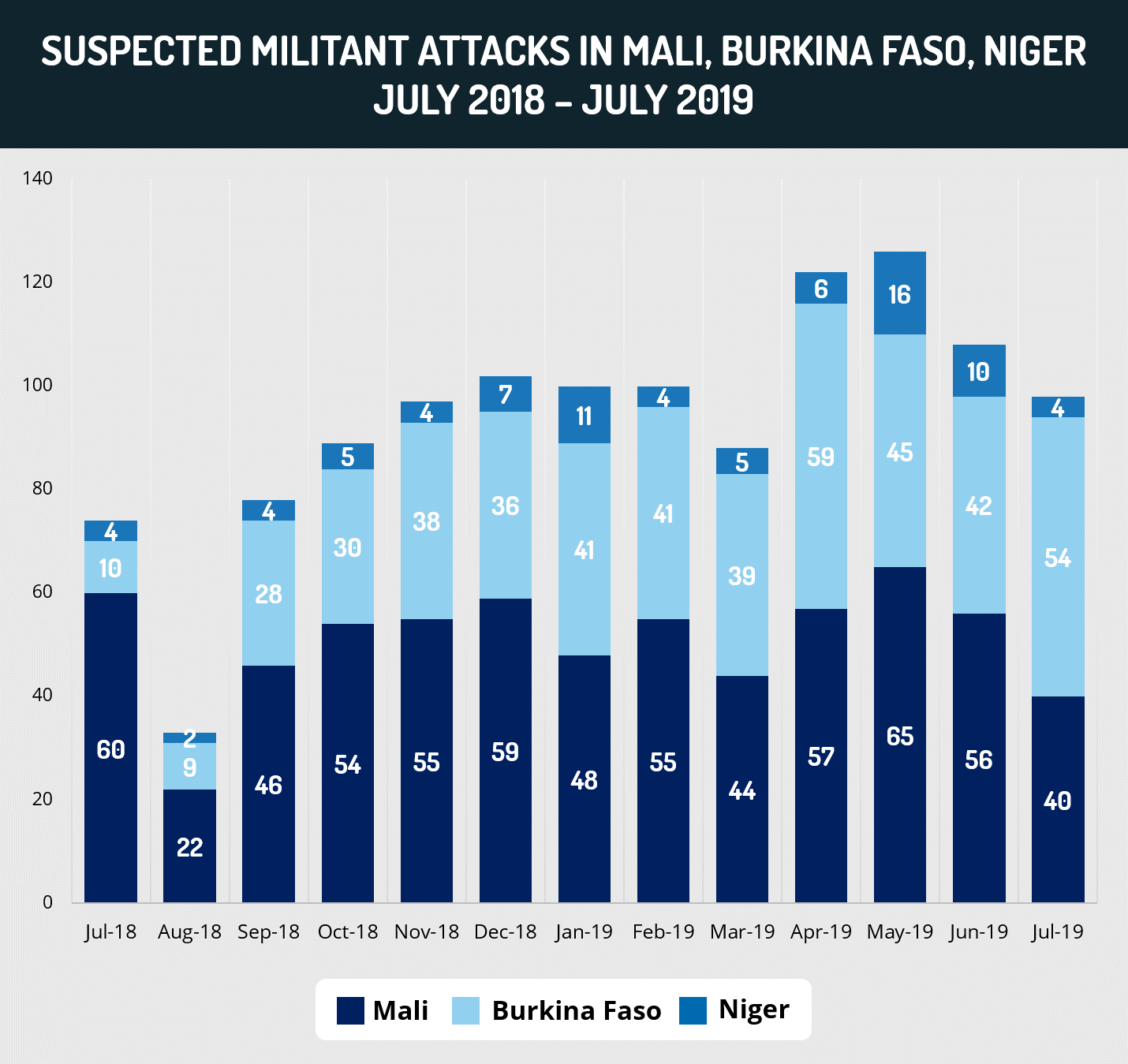

Although France and Mali are expected to tout this as a success, which will further justify France’s increasingly unpopular presence in the Sahel, this is nonetheless not expected to disrupt militancy in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

Current Situation

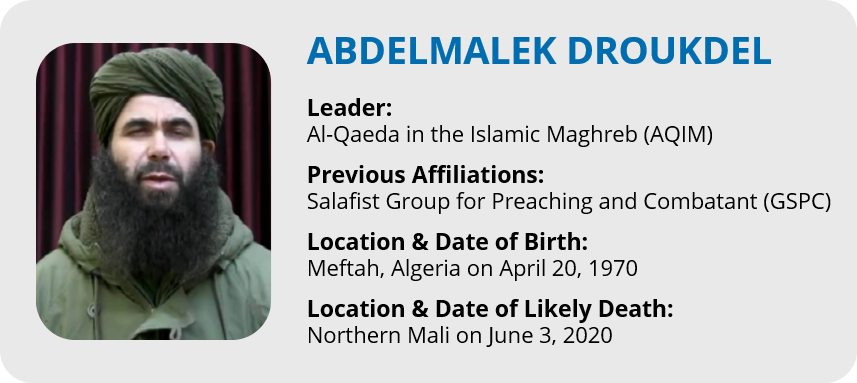

On June 5, France’s Minister of the Armed Forces Florence Parly stated that French forces with the “support of partners” killed the Emir of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Abdelmalek Droukdel, also known as Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud, along with “several of his close collaborators” at an unspecified location in northern Mali on June 3.

Reports indicate that Droukdel was killed in Talhandak in Mali’s Kidal Region, close to the border with Algeria.

On June 6, reports emerged that al-Qaeda jihadists and supporters were eulogizing Droukdel in internal communication, but as of the time of writing, no announcement was officially published by al-Qaeda.

The US Africa Command (AFRICOM) issued a press release on June 8 acknowledging France’s announcement and further stating that AFRICOM has confirmed Droukdel’s death in an independent assessment.

Background

Abdelmalek Droukdel was the Emir of AQIM, formerly known as the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combatant (GSPC), which was an offshoot of the Armed Islamic Group (GIA), which fought in the Algerian civil war of the 1990s. Droukdel assumed the leadership of the GSPC in mid-2004 and pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden in September 2006. In 2007, the GSPC was officially renamed as AQIM. Droukdel is considered one of the founding members of AQIM and held a highly symbolic position within the group’s hierarchy, also due to his direct ties with Osama bin Laden, as well as his previous involvement in the Afghan civil war.

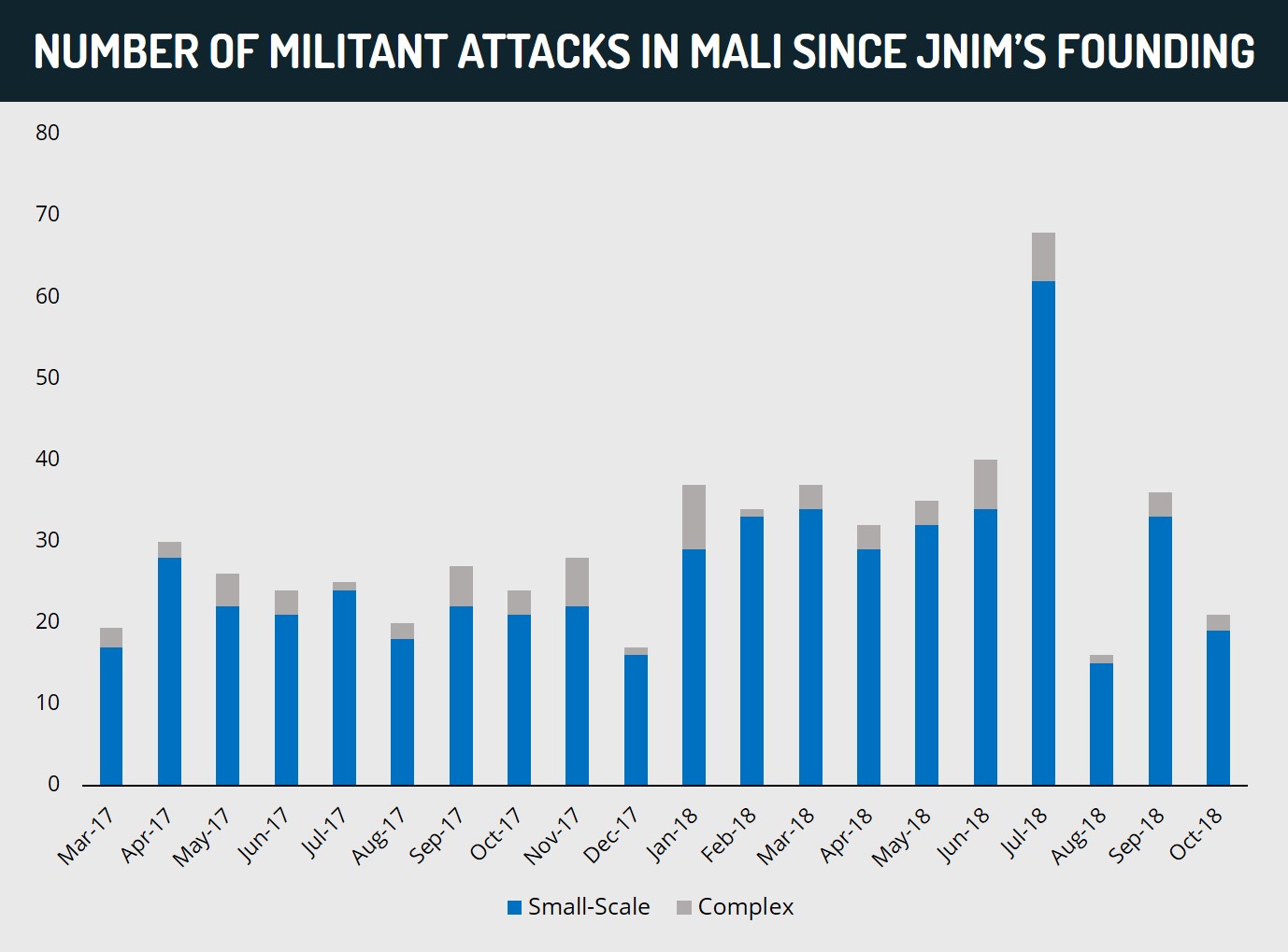

Under Droukdel, AQIM supported several jihadist movements in other parts of Africa, particularly Mali, where several AQIM affiliates formed from 2011 onward. In March 2017, AQIM’s Sahara branch, al-Mourabitoun, Ansar Dine, and Macina Liberation Front announced that they would be unifying under a single al–Qaedacoalition, Jamaat Nusrat al–Islam waal Muslimeen (JNIM), with Ansar Dine leader Iyad ag Ghali as its leader. In 2014, Droukdel also sponsored a merger betweenAnsar al–Sharia in Tunisia (AST) and the Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade (OIB), two local jihadist groups that were outlawed by the Tunisian government. Over recent years, AQIM has almost completely shifted its center of gravity from Algeria toMali due to intensive counter-militancy operations by the People’s National Army (ANP) in Algeria. JNIM is now the strongest al-Qaeda group in the region, with Algeria serving mostly as an auxiliary effort. AQIM’s remaining presence in Algeria can mainly be attributed to Droukdel’s historical ties to the country and his effort to restore the lost prestige of the organization.

Although AQIM did not officially confirm Droukdel’s death and France has in the past prematurely claimed to have killed high-level al-Qaeda leaders in the Sahel such as Amadou Kouffa, the leader of the JNIM constituent Katiba Macina, there is a strong likelihood that Droukdel was in fact killed. This is supported by the reported internal communication between al-Qaeda members and the duration of time between when the incident occurred and when it was announced by France and then the US, which may have gone at least in part to confirm the successes of the operation, as well as the fact that it was officially announced by both countries.

Assessments & Forecast

Loss of Droukdel likely to adversely impact AQIM operations in Algeria, Tunisia, possibly trigger slight resurgence in IS activity in Algeria

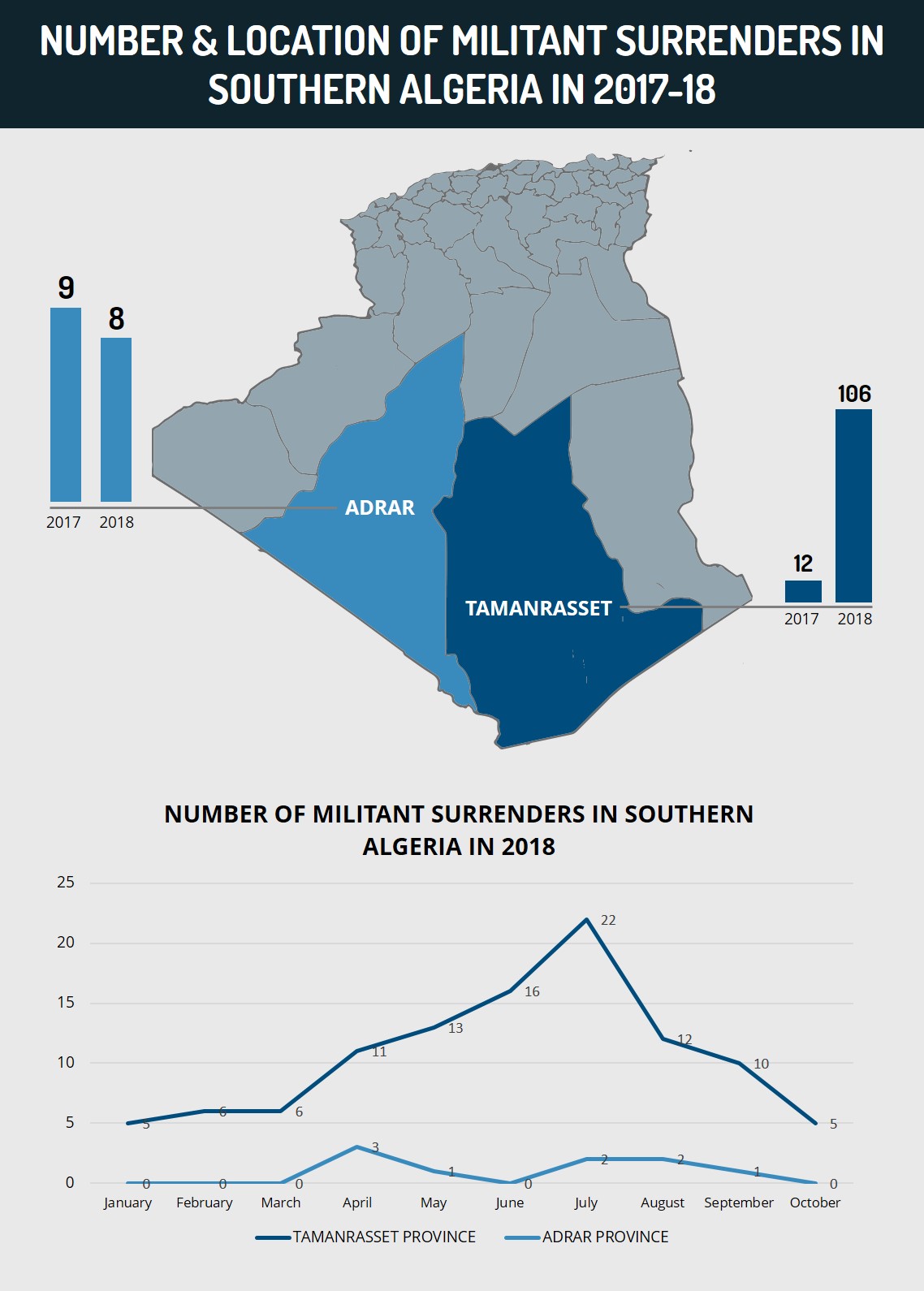

AQIM activity in Algeria has significantly declined over recent years amid successful counter-militancy operations by the People’s National Army (ANP), most recently aggravated by the ANP killing ten of the militant group’s local leaders during counter-militancy operations in the northeastern Jijel and Skikda provinces in 2018. This resulted in militant attacks becoming rare and small-scale when they do occur, with AQIM itself not claiming responsibility for an attack in the country since August 31, 2017, when it claimed a suicide bombing against a security headquarters in Tiaret. Due to its continued operational constraints, the jihadist group was forced to operate in a highly decentralized fashion in Algeria, with local leaders having more influence over the group’s on-ground tactics and activities. Leaders, such as Droukdel, who are much higher in the group’s hierarchy, are generally involved in outlining the group’s ideology and overarching goals, while also acting as symbolic figures for the group’s fighters. FORECAST: Therefore, while Droukdel’s death will not have any immediate direct impact on AQIM’s on-ground capabilities in Algeria, it nonetheless constitutes a significant symbolic loss, which would therefore have a long-term negative effect on its capabilities in North Africa.

Despite the decline in operations, militants and their infrastructure remain entrenched in Algeria’s northern outlying areas, which is underscored by near-daily discovery of hideouts and weapons caches, as well as arrests of militants and their supporters. Furthermore, the ANP frequently discovers caches of weapons, which likely originate from Libya, along Algeria’s southern borders, that are likely mostly intended to be transferred into the Sahel, which indicates the continued connection between operations in Algeria and the Sahel. However, it is possible that some of these weapons are diverted toward maintaining activities in Algeria. FORECAST: As Droukdel was the most prominent historical and symbolic link between AQIM and Algeria, his killing may prompt al-Qaeda to reduce the investment of resources in Algeria, which may be perceived as wasteful given the group’s inability to act there, and shift it entirely toward the Sahel, where it has been much more successful in recent years.

This, in turn, may have an adverse impact on AQIM-affiliated OIB’s operations in western Tunisia. Since the construction of a border obstacle between Tunisia and Libya, smuggling activity between the countries reduced significantly, leading to OIB supply lines from Libya to be extended through Algeria and facilitated by and dependent on AQIM’s operations there. FORECAST: Therefore, if AQIM were to divert resources away from Algeria toward the Sahel, in the long term, this will also constrict AQIM-affiliated OIB’s supply lines and reduce its operational capabilities in Tunisia. Nonetheless, in the short term, a decrease in focus on operations in Algeria may mean that whatever assets are still left in the country would be diverted to support OIB in Tunisia, which despite its own significant challenges, is still considered more successful in recent years than the group in Algeria.

FORECAST: This development will also have a negative effect on the morale of AQIM fighters across the Maghreb, as the militant group’s prestige in the North Africa region diminishes with the increased diversion of resources and focus of operations toward the Sahel. This will make it difficult for AQIM to attract additional recruits and support from among segments of the local population of Algeria and Tunisia. The Islamic State (IS), which maintains a limited operational presence in Algeria and Tunisia, may attempt to capitalize upon this dynamic to attract AQIM fighters to bolster its ranks. IS is specifically known to maintain at least some capabilities in southern Algeria. This is evidenced by the IS-claimed vehicle-borne IED (VBIED) attack targeting a military facility in Bordj Badji Mokhtar Province’s Timiaouine on February 9 as well as the IS-claimed killing of eight ANP soldiers during clashes in Tamanrasset Province’s Taoundart on November 21, 2019. Both incidents involved militants with links to IS in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), which is active in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Regardless, a decrease in AQIM activity in Algeria may provide IS militants with a greater degree of operational freedom in southern Algeria due to the lack of competition.

FORECAST: There has also been an increase in IS activity in southern Libya in May and June following a lull in operations by the militant group over the past year. This has mainly been facilitated by the security vacuum that has been created in southern Libya due to Libyan National Army’s (LNA) increased diversion of resources toward northwestern Libya for its offensive against the Government of National Accord (GNA)-linked forces. This has provided IS militants in southern Libya with a greater degree of freedom of movement and operations. However, despite this recent increase in IS activity in Libya, the militant group’s capabilities in terms of personnel and infrastructure are still limited, as underscored by the small-scale nature of most of its recent attacks as well as various other video publications released by the group that showcase a limited number of fighters in the country. Nevertheless, AQIM’s decline could present IS with an opportunity to expand from Libya into southern Algeria. However, IS has not yet shown any indication that it is interested in such a strategy, and Algeria’s border with Libya is relatively more secure than that with Mali and Niger. Hence, even if IS is interested in expanding from Libya into Algeria, this risk is slightly lower.

Droukdel’s killing unlikely to have significant operational impact on JNIM activities in Sahel, expected to be portrayed as victory for counter-militancy efforts by France

Even though the death of Droukdel is a very notable symbolic blow to al-Qaeda in North and West Africa, its spiritual impact in the Sahel is likely to be somewhat limited given that JNIM and AQIM in Algeria have grown more distant in recent years. Over time, the high-profile leadership, as well as the constituency, of the al-Qaeda outfit in the Sahel has become more local. This wedge between al-Qaeda in the Maghreb and the Sahel was further aggravated after leaders of AQIM’s Sahara branch, Yahya Abou Hammam and Abu Abd al–Rahman al–Sanhaji, also known as “Ali Maychou”, who were central figures in the establishment of JNIM, were killed by France in 2019.

Given this growing distance, it remains unlikely that Droukdel’s death will translate into a substantial operational impact or reduced militant capabilities in the Sahel. AQIM’s control over its branches is decentralized while the Sahara branch of the organization is just one of the components that form JNIM, where the different constituent groups maintain their own spheres of influence. This suggests that while there exists some potential for the operations of the Sahara branch of AQIM to be slightly affected in Droukdel’s absence, the operations of the larger coalition are likely to continue unhindered under the direction of the leader of JNIM constituent Ansar Dine, Iyad ag Ghali, as well as the leader of Katiba Macina, Amadou Kouffa.

In fact, rather than Droukdel’s death detrimentally impacting on-ground militant capabilities, it is possible that JNIM will see operational benefits as resources may be diverted from al-Qaeda outfits in Algeria and Tunisia to Mali and Burkina Faso in the long term. FORECAST: Regardless, the trend of militancy in the Sahel is expected to persist. Additionally, it remains possible that attacks directed toward French Barkhane forces, who are attractive targets for militants, will see an uptick in the coming weeks in symbolic retaliation for the death of Droukdel.

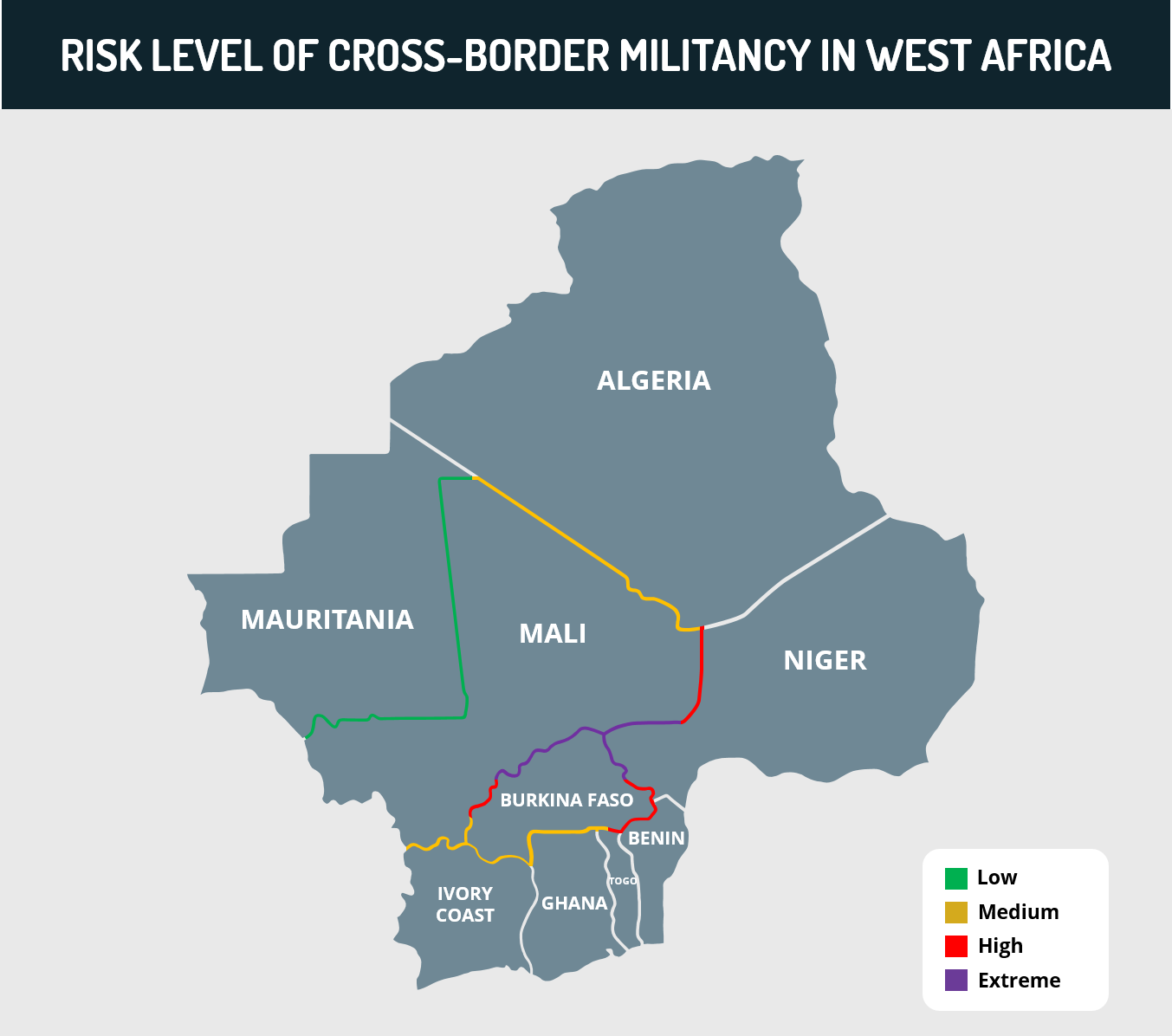

Nonetheless, due to Droukdel’s status, his killing in northern Mali marks a momentous symbolic victory for counter-militancy efforts in the Sahel. The French, who have been facing mounting criticism from the populations of the Sahelian countries, are likely to capitalize on the success of this airstrike to justify their continued operations in the tri-border region between Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. The perception of success following this operation is particularly important due to JNIM’s acceptance of the Malian government’s offer for a dialogue on March 8, contingent upon the withdrawal of international forces. The Malian government has not yet responded to JNIM’s conditional acceptance, likely due to the blow that the withdrawal of French forces would pose to counter-militancy efforts in Mali.

FORECAST: Considering that the killing of Droukdel is going to be presented as a great success by the French and Malian authorities, it is likely that the government’s pro-French position will become further entrenched following this operation. Conversely, given French leadership of the operation, should the government attempt to negotiate the conditional acceptance, JNIM is likely to be unyielding in their demand for the withdrawal of French forces. This has the potential to further exacerbate dissatisfaction among the Malian populace who have been clamoring for a dialogue with the jihadists as well as widen the political divide where a coalition of opposition parties held a large-scale march on June 5 demanding the resignation of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita.

FORECAST: Ultimately, the center of gravity of al-Qaeda activities had already moved from Algeria to the Sahel, and going forward, given the decentralized nature of al-Qaeda operations, there is unlikely to be any significant change in militancy in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. While there remains a chance that the international and national militaries will launch bolstered offensives to press their perceived advantage accorded by Droukdel’s death, it is unlikely to significantly affect JNIM activities beyond the near-term.

Recommendations

Maghreb

Travel to Algiers, Oran, and Tunis may continue while adhering to all security precautions regarding militancy and civil unrest. Consult with at [email protected] or +44 20-3540-0434 for itinerary and contingency support options.

We advise against all nonessential travel to Algeria’s outlying areas. Those conducting business essential travel to the region are advised to avoid nonessential travel to the mountainous parts of northern Algeria’s outlying areas due to the underlying threat of militant activity. Consult with us for itinerary-based travel recommendations and ground support options.

It is further advised to avoid all travel to the vicinity of Algeria’s borders with Mali, Niger, and Libya due to the increased threat of militant activity in these regions.

Avoid all travel to Tunisia’s Kasserine, Kef, and Jendouba governorates, in addition to all border areas, due to jihadist activity and military closures. Furthermore, avoid all travel to within 50 km from the border with Libya, due to the threat of attacks originating from Libya targeting Tunisian interests.

Sahel

We advise against all travel to the border region between Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, given the extreme risks of militancy, ethnic conflict, and violent crime.

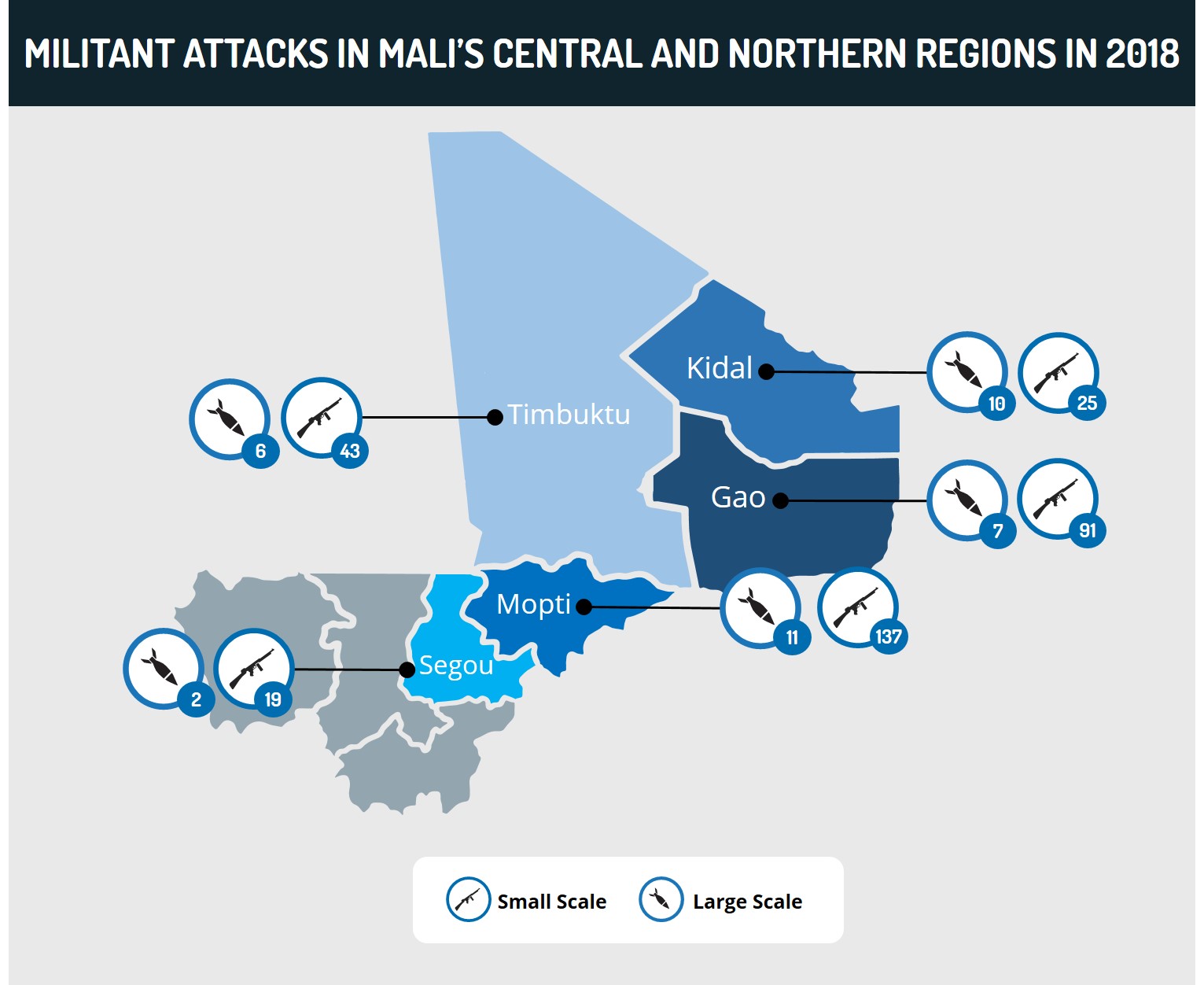

Avoid all travel to northern and central Mali, including Timbuktu, Kidal, Gao, Mopti, and northern Segou region, given the threat from militant and rebel groups operating in the area, as well as ongoing ethnic tensions and intercommunal violence.

Maintain heightened vigilance in Mali’s Koulikoro, Kayes, and Sikasso regions due to the rapidly expanding militant operational theater and growing insecurity.

Avoid all travel to northern and eastern Burkina Faso, particularly Sahel, Est, Centre-Est, Nord, Centre-Nord, and Boucle du Mouhoun regions due to the ongoing threat of militancy and violent crime. Avoid nonessential travel to outlying areas of the southern and western regions due to the increased risk of attacks.

We advise against all travel to Niger’s Tillaberi and Tahoua Regions in the west along the borders of Mali and Burkina Faso, with the exception of Niamey, due to the ongoing risk of militancy.